Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Lokeshvara — The One Who Hears the World

In the Mahayana imagination, compassion is not sentiment. It is labour.

It is the decision to remain where the cries are still audible.

Lokeshvara—also known across the Buddhist world as Avalokiteshvara—is the Bodhisattva who turns back at the threshold of release. Having reached the clarity that would permit full buddhahood, he refuses the final step. He remains suspended between worlds, not through hesitation, but through vow. The suffering of beings, it is said, was louder than liberation.

In Sanskrit, Avalokita means “to look down,” to attend, to observe with care. In Khmer devotion, Lokeshvara becomes Lokesvara: Lord of the World, the one who bears the weight of the human realm not as dominion, but as responsibility. His authority is not sovereign; it is responsive. He does not rule the world. He listens to it.

This listening defines his form. Tradition tells that Amitabha, the Buddha of Infinite Light, granted Lokeshvara eleven heads, so that no cry—near or distant, human or otherwise—could go unheard. He was given a thousand arms, each ending in an open palm, so that aid might arrive before despair had time to harden. Compassion, in this vision, is not singular. It is distributed. It multiplies itself in order to reach.

In Khmer sculpture, Lokeshvara most often appears as a youthful figure, slender and poised, holding a lotus bud in his left hand. The lotus is not yet open. It promises awakening, but does not claim it. At his crown sits the small, meditating figure of Amitabha, reminding the viewer that compassion is not separate from wisdom, but wisdom expressed outward, in motion, among others.

During the reign of Jayavarman VII, Lokeshvara moved from sanctuary to centre. Never before, and never again, would the Bodhisattva of Compassion occupy such a dominant place in the religious and political life of Angkor. Jayavarman VII did not merely patronise Lokeshvara; he patterned his rule upon him.

The king’s inscriptions are unambiguous: “The suffering of the people is the suffering of kings.” This was not metaphor. It was policy. Hospitals were built—one hundred and two of them—across the empire. Rest houses lined the royal roads. Care, shelter, and healing were formalised as acts of governance. Compassion became infrastructure.

At Neak Poan, this ethic takes architectural form. The temple sits at the centre of the Jayatataka baray, conceived as a living mandala of healing. Its central island rises like a lotus from the water, recalling the mythical Lake Anavatapta, whose waters were believed to cleanse both disease and moral stain. Here, Lokeshvara appears not as judge or saviour, but as physician—one who restores balance rather than pronounces absolution.

A sculpture of the flying horse Balaha, a manifestation of Lokeshvara, once stood within these waters. In the legend, the Bodhisattva takes this form to rescue shipwrecked merchants from an island of man-eating demons, carrying them across the ocean of peril to safety. The image is exact. Compassion is not passive. It carries.

Nowhere is the fusion of devotion, lineage, and statecraft clearer than at Preah Khan, dedicated by Jayavarman VII to his father, Dharanindravarman II, deified in the likeness of Lokeshvara. The king’s mother, enshrined at Ta Prohm as Prajnaparamita—the Perfection of Wisdom—completed a triad in which Wisdom and Compassion give birth to Enlightenment, embodied in the Buddha at the Bayon, with whom the king himself was identified.

This was not abstraction. It was a deliberate reordering of the cosmos, inscribed into stone and water. Compassion was no longer a private virtue. It became the organising principle of empire.

At Banteay Chhmar, Lokeshvara appears with a thousand arms, radiating outward across the temple walls. Each arm is distinct, yet all move in the same direction: outward, toward others. The image resists hierarchy. There is no single centre from which compassion flows. It arises everywhere at once.

Some Khmer representations go further still, depicting a radiating Lokeshvara, his body covered in thousands of tiny Buddhas, as though compassion itself had become contagious—replicating, multiplying, refusing containment. In these images, there is no boundary between the Bodhisattva and the beings he saves. The world is carried within his skin.

To stand before such figures today, in the half-light of Angkor’s galleries, is to encounter a theology carved from responsibility. Lokeshvara does not promise escape from the world. He promises accompaniment within it. He hears because he remains close enough to listen.

Compassion, here, is not an emotion. It is a posture.

A refusal to turn away.

A vow to stay.

Also in Library

The Immune System of Love

2 min read

A meditation on anger as sacred intelligence — the moment love refuses disappearance and becomes protection. Written from the hush between endurance and clarity, this poem explores the quiet transformation where gentleness discovers its boundary and survival becomes an act of care.

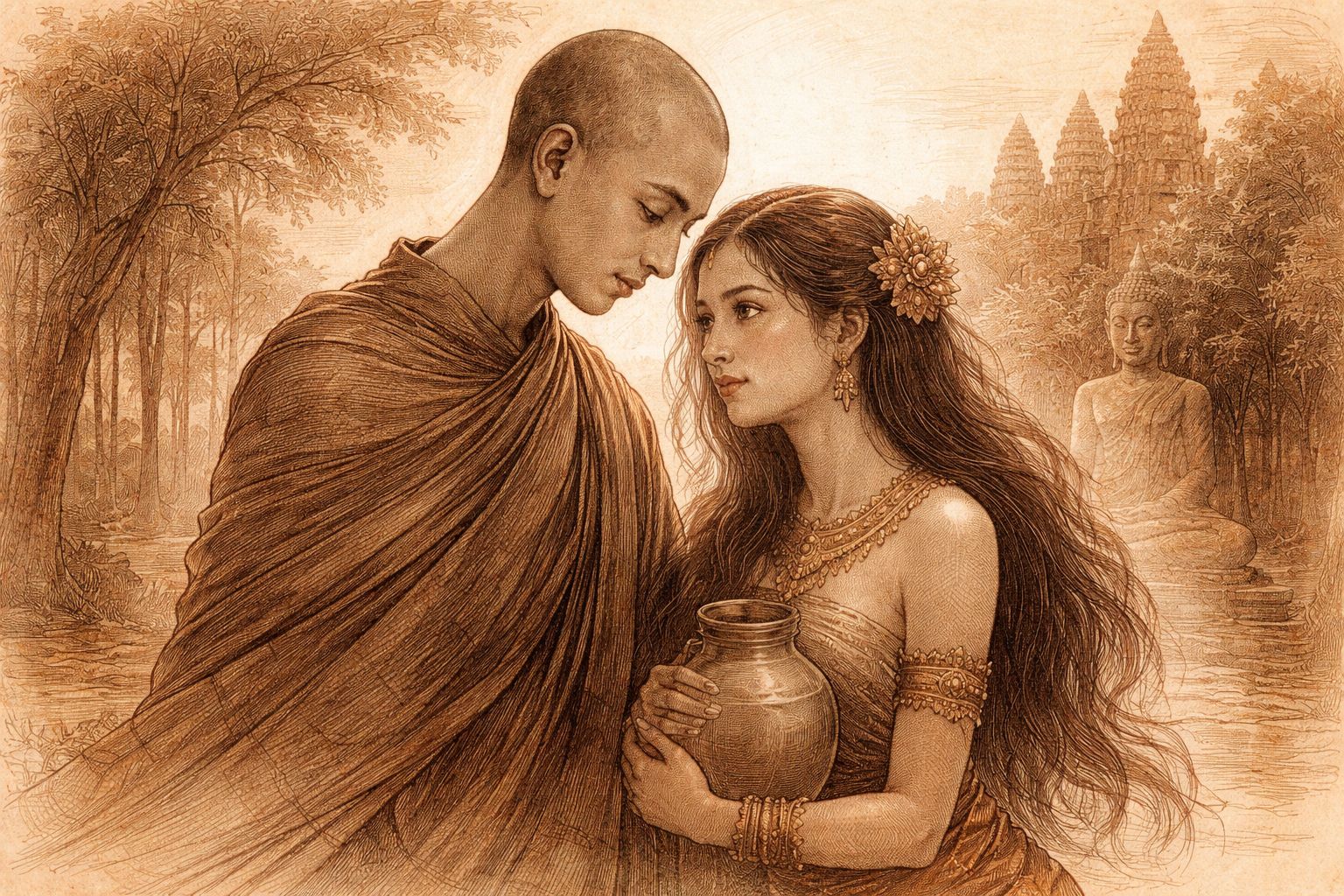

The Robe and the Lotus

2 min read

A monk and a girl do not touch.

The law speaks louder than breath.

Their names pass mouth to mouth, like prayer.

This bilingual poem is offered in the spirit of a Khmer tragic love story—where devotion survives prohibition, and grief becomes a form of listening.

Salt-Wife at the Rain Gate

3 min read

In a year of drought, a woman comes from the flats and asks for a vow instead of rain. Salt is withheld. Water arrives only by measure. A gate listens. This is not a story about abundance, but about keeping—what land, seasons, and people owe each other when gifts are no longer enough.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.