Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

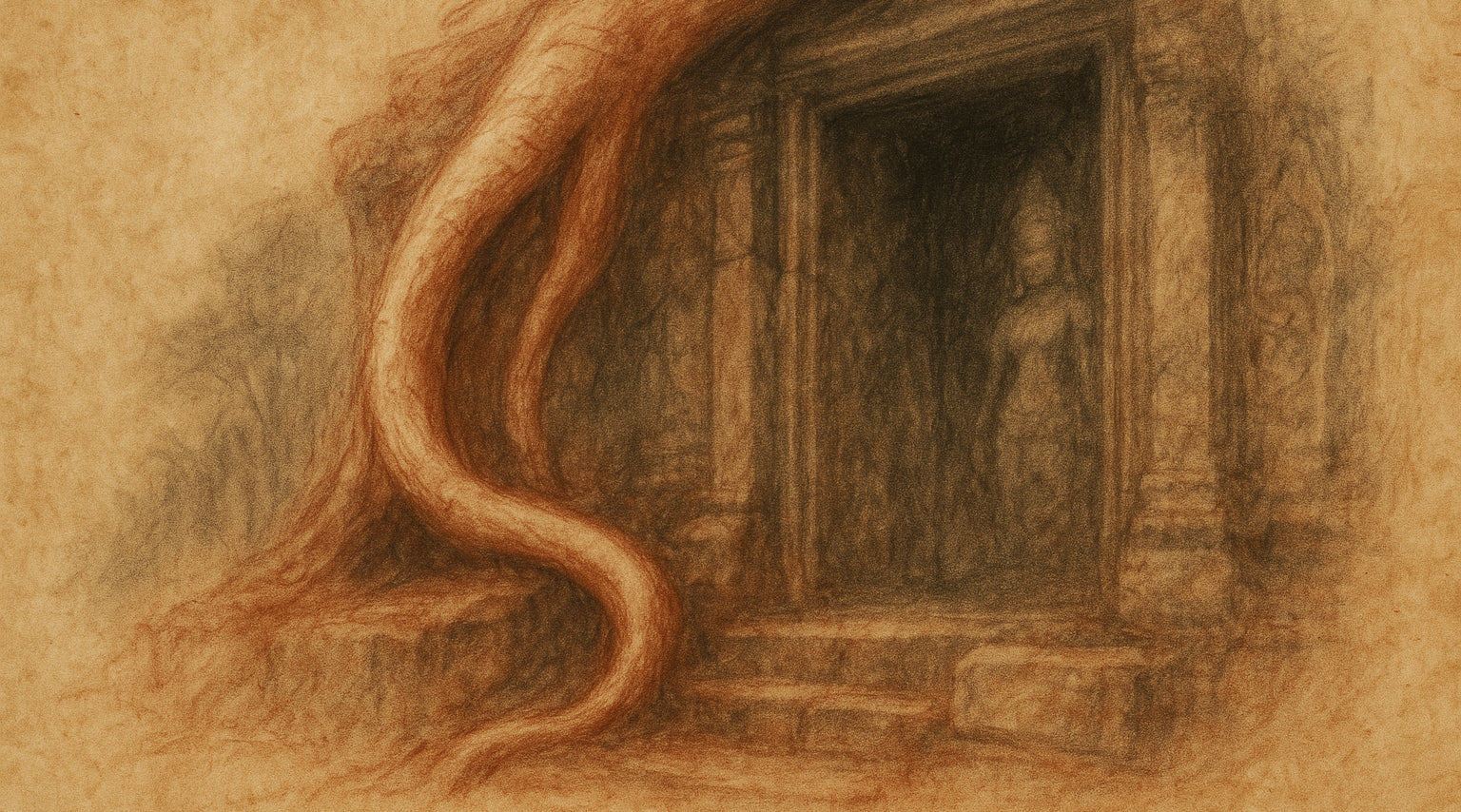

The Beauty That Time Reveals

Sanctuary of Meaning · Artist’s Journal

“What is made perfect loses the breath.

What is left undone opens the soul.”

—from a field note near the southern gopura of Ta Prohm

—

There are many ways to define beauty.

In the West, we often chase it through geometry. We seek it in symmetry, in the closed logic of circles and squares, in the unblemished sheen of things that do not change. From the Parthenon to modern towers of glass, the ideal form has long been smooth, sharp, and untouched by time—as though beauty were a triumph over nature, rather than a deepening within it.

And yet, as I stood in the shadow of an ancient temple at Angkor, fingers tracing a weathered stone softened by centuries of rain, I realised that my heart did not stir for perfection. It stirred for something else entirely.

Not the polished, but the worn.

Not the flawless, but the fractured.

Not the finished, but the becoming.

It was in Asia, decades ago, that I first learned the word for this quiet reverence: wabi-sabi.

An ancient Japanese aesthetic philosophy, wabi-sabi honours impermanence, imperfection, and incompletion. It does not look away from erosion or asymmetry. It bows to them. It sees the unfinished as luminous, the weathered as wise, the overlooked as sacred. This sensibility—subtle as breath, deep as silence—reshaped not only how I create, but how I see.

There are seven principles that guide the spirit of wabi-sabi, and I return to them often, like mantras. Not only in my work, but in the rhythm of my life.

Kanso (簡素) – Simplicity. The clarity that arises not through addition, but subtraction. To remove the unnecessary so the essential can breathe. When I compose, I do not embellish. I listen. I pare down until what remains feels inevitable.

Fukinsei (不均整) – Asymmetry. Western thought often fears imbalance. But nature never does. The enso—the Zen circle—is drawn incomplete, an open gesture toward the infinite held within imperfection. I have learned to let compositions lean, tilt, meander—to find stillness through irregular grace.

Shibui (渋味) – Understatement. Beauty that does not shout. Poetry that does not explain. A thing is most itself when it is simply, precisely, what it was meant to be—no more, no less. In my prints, I strive for articulate brevity, elegant restraint. As Leonard Koren reminds us: “Pare down to the essence, but don’t remove the poetry.”

Shizen (自然) – Naturalness. Not rawness, not accident, but an unforced unfolding. Like the Japanese garden that appears spontaneous yet is meticulously shaped, I seek a similar truth in my compositions: to feel inevitable, though gently guided. To seem as though they simply appeared.

Yūgen (幽玄) – Mystery. That which is unseen opens more than what is shown. The temples of Angkor are masters of suggestion. A half-lit corridor, a figure turned away, the shadow of an apsara across the wall—each hints at the invisible. I try never to reveal too much. I let silence speak.

Datsuzoku (脱俗) – Freedom. From habit, from convention, from the known. This is the spirit of surprise—the moment when something deviates from the expected and awakens us. In those moments, I feel most alive.

Seijaku (静寂) – Tranquillity. Not lifeless stillness, but a charged calm. Like the hush before dawn. Like the silence that rises at Angkor when the jungle holds its breath. This is the atmosphere I long to preserve in every image: a quiet that pulses with presence.

Wabi-sabi is not a style. It is not “minimalism,” though the word is often reached for. It is a way of seeing—and of being—with the world. A way of kneeling before what is fleeting, and whispering: You are enough. Even now.

At the temples of Angkor, wabi-sabi becomes not just a lens, but a revelation. These ruins are beautiful not despite their decay, but because of it. The patina of time does not diminish them—it sanctifies them. The cracks, the lichen, the stains where rain has lingered for centuries—these are not flaws. They are memory. They are offering.

Even the most exquisite carvings were once in flux. Every lintel began as rough stone. And all around, life continues to begin again: roots seeking shadowed crevices, moss unfurling across fallen plinths, birds etching circles into the morning light. There is no stillness here that is not alive.

It is the texture of time—its wear, its transformation—that invites the imagination to enter. Perfection closes the door. Wabi-sabi leaves it open.

And so I work not with the fantasy of the untouched, but with the truth of what endures.

Not polished, but breathing.

Not final, but faithful.

Not eternal, but deeply, vulnerably here.

—

Coda:

The beauty that does not ask to be seen is the one that remains.

—

Also in Library

The Devata at First Light

8 min read

At first light in Banteay Kdei, a devata draws the eye into stillness. Through sanguine chalk, black shadow, and repeated returns to the page, sketch and prose slowly deepen into a single act of devotion—until the words, too, learn how to remain.

The Spark and the Weight of Being Human

9 min read

At some point in our past, a human asked the first question—and self-awareness was born. Yet the same consciousness that gave us power also confronts us with our limits. This essay explores the paradox of being human: the spark of understanding and the weight of knowing.

The Pact of the Uncounted Grain

10 min read

A village does not starve only when rice runs out. It begins to thin when everything is counted, explained, and held too tightly. The Pact of the Uncounted Grain remembers an older law: that once each season, abundance must pass through human hands without measure, or the world begins, quietly, to lose its meaning.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap — reflections, field notes from the temples of Angkor, and glimpses into the writing and creative life behind the work.

When you subscribe, you will receive a complimentary digital copy of

Three Ways of Standing at Angkor — A Pilgrim’s Triptych, a short contemplative book on presence, attention, and the art of standing before sacred places.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet words, delivered gently.

Subscribe and step into the unfolding journey.