Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Jayavarman I — Armour of the Centre

3 min read

Before Angkor learned to rise in stone, it learned to gather itself in will.

Jayavarman I stands at that inward moment. Not yet empire, not yet monument—only the difficult act of holding. His reign belongs to the seventh century, to the pre-Angkorian world the Chinese would call Chenla, but its true location is not merely geographic. It lies in the discipline of centre: the attempt to draw scattered lands, rival lineages, and inherited powers into a single, defended core.

His name already speaks the ambition. Jaya—victory. Varman—armour. Not conquest for its own sake, but protection through strength. A king as casing, a ruler as shell. In a landscape fractured by local overlords and ancestral claims, Jayavarman I did not rule by charisma alone. He ruled by measure, appointment, decree. Power was no longer simply inherited or regional; it was named, recorded, enforced.

From Purandarapura, near the great inland sea of the Tonle Sap, his authority stretched widely—north to the highlands around Wat Phu, south toward the gulf. Yet this breadth was not sustained by constant movement or spectacle. It was sustained by administration. Jayavarman I replaced local hereditary chiefs with royal officials. He issued edicts concerning land and temples that carried explicit threats for disobedience. Titles multiplied, offices hardened, hierarchies took shape. The state began to speak in its own voice.

For the first time, a Khmer king was addressed as vrah kamraten an—Holy Lord—while still alive. The title signals something profound: sovereignty was no longer merely ancestral or martial. It was becoming sacralised in the person of the ruler himself. The king was not only chosen by lineage or victory, but by order.

Religion under Jayavarman I did not narrow; it consolidated. Shiva and Vishnu stood side by side in the sanctuaries he endowed. Older currents—Buddhist, Hindu, local—were not erased so much as subordinated to royal supervision. Faith, like land, was drawn inward, brought under watch. Even the reports of destruction recorded by Chinese pilgrims speak less of fanaticism than of reorganisation: the replacement of autonomous religious life with state-aligned cult.

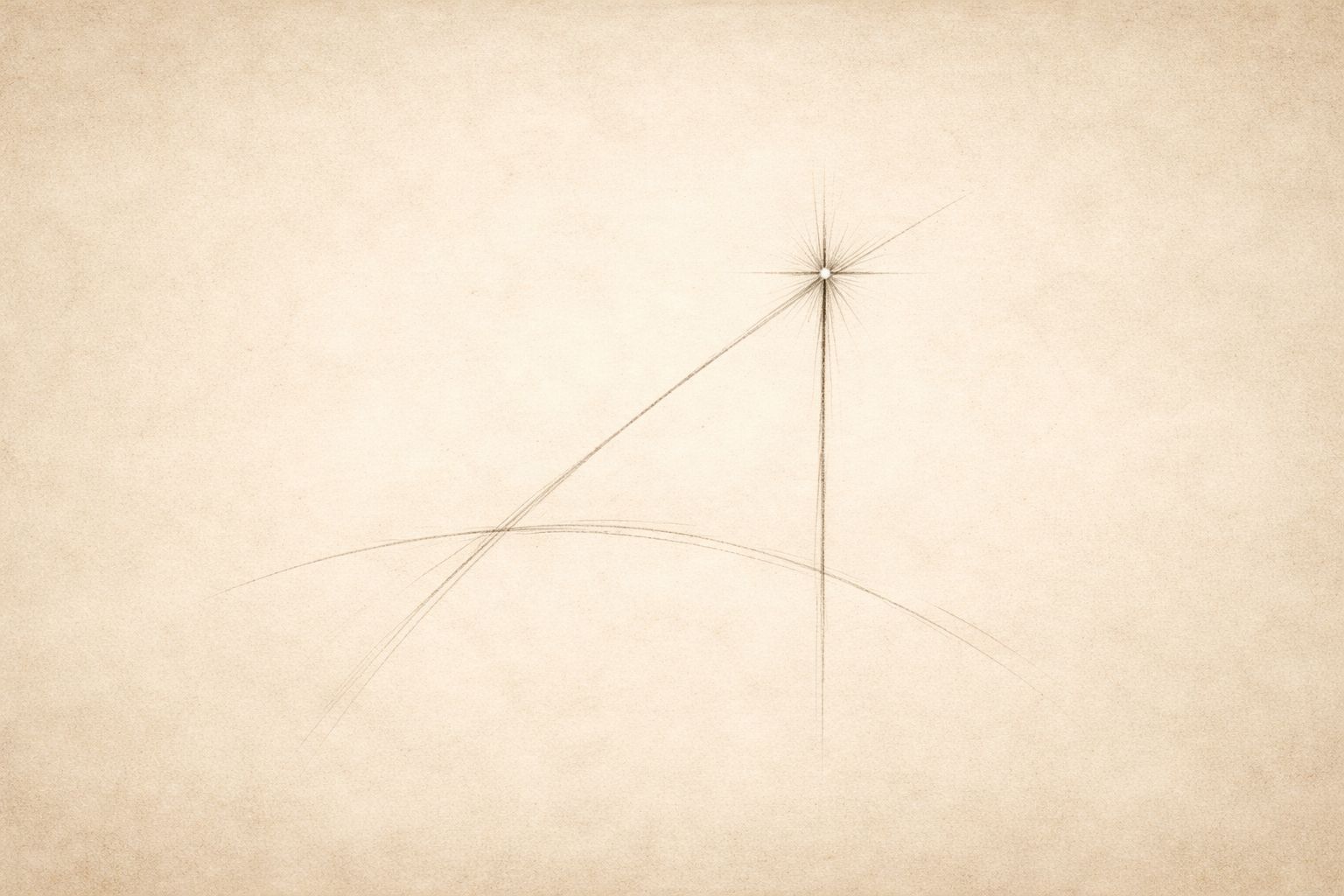

At Ak Yum, a modest brick structure rose—early, experimental, almost tentative. Yet within it lies the seed of Angkor’s future: elevation, axis, centre made visible. The temple-mountain was not yet perfected, but the idea had been planted. Architecture, like governance, was learning to stack meaning vertically.

Jayavarman I’s achievement was therefore not splendour but coherence. He reunited what his great-grandfather had once ruled, then attempted something more difficult: to prevent it from fragmenting again. In this he ultimately failed—not through weakness, but through succession. He left no male heir. After his death, his daughter Jayadevi ascended the throne, and the system he had built began to loosen. Chinese sources would later describe the realm as divided into “Land” and “Water” Chenla—a poetic way of naming political fracture.

The armour cracked.

Yet the failure does not undo the act. Jayavarman I demonstrated that Cambodia could be governed as a centre, not merely inhabited as a landscape. He proved that authority could be bureaucratic, sacral, and territorial at once. Later kings would inherit his insight and clothe it in stone, ritual, and cosmic geometry.

Angkor’s towers were still centuries away. But their discipline—the insistence on axis, order, and guarded centre—was already present. It lived briefly, rigorously, in a king who understood that before a civilisation can build upward, it must first hold itself together.

Also in Library

The Spark and the Weight of Being Human

9 min read

At some point in our past, a human asked the first question—and self-awareness was born. Yet the same consciousness that gave us power also confronts us with our limits. This essay explores the paradox of being human: the spark of understanding and the weight of knowing.

The Pact of the Uncounted Grain

10 min read

A village does not starve only when rice runs out. It begins to thin when everything is counted, explained, and held too tightly. The Pact of the Uncounted Grain remembers an older law: that once each season, abundance must pass through human hands without measure, or the world begins, quietly, to lose its meaning.

A Manifesto for Modern Living

3 min read

The old certainties have weakened, yet the question remains: how should one live? This manifesto explores what it means to create meaning, think independently, and shape a life deliberately in an uncertain world.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap — reflections, field notes from the temples of Angkor, and glimpses into the writing and creative life behind the work.

When you subscribe, you will receive a complimentary digital copy of

Three Ways of Standing at Angkor — A Pilgrim’s Triptych, a short contemplative book on presence, attention, and the art of standing before sacred places.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet words, delivered gently.

Subscribe and step into the unfolding journey.