Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Jayavarman II — The Mountain That Remembered His Name

Some rulers conquer land. Others re-align the world.

Jayavarman II does not arrive in history with monuments already standing in his name. He arrives into fracture—into a landscape of rival lords, migrating courts, and memories of foreign dominance that still cling like humidity to the lowlands. What he brings is not yet stone, but direction. Not an empire, but an axis.

Born in 770, Jayavarman II emerges from a period in which Cambodia has forgotten how to stand as one body. Power exists everywhere and nowhere at once, dispersed among regional rulers whose authority is local, provisional, and fragile. The name he bears—Jayavarman, victorious armour—signals his intent. Victory here is not mere conquest. It is enclosure: the act of giving a people a boundary they can recognise as their own.

The chronicles say he comes from Java, though the word itself resists precision. Island, peninsula, rival court, or symbolic elsewhere—what matters is not geography, but return. Jayavarman II re-enters Cambodia carrying the burden of separation and the task of undoing it. His early reign is restless. Courts shift. Alliances form and dissolve. Authority moves like a probing hand across the land, testing where it can take hold without breaking.

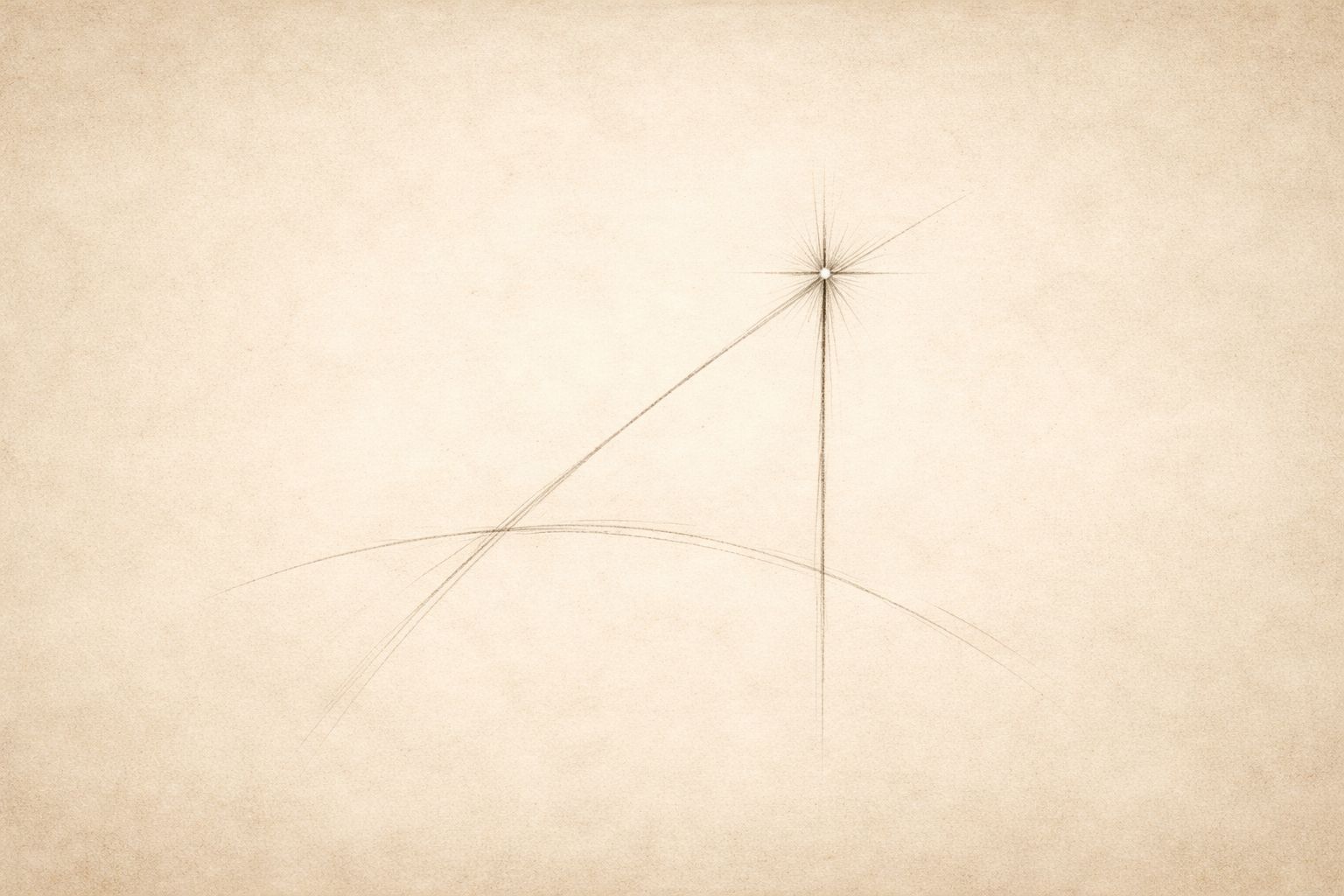

The decisive moment comes in 802 CE, high on the plateau of Phnom Kulen, then known as Mahendraparvata—the Mountain of Indra. Here, above the floodplains and beyond the reach of any single rival lord, Jayavarman II performs a ritual that is as political as it is sacred. He is proclaimed cakravartin: universal monarch. Not king among kings, but centre among centres.

This is not theatre. It is engineering.

Assisted by the Brahmin Hiranayadama, Jayavarman II institutes the devaraja—the “god who is king.” Later misunderstandings would flatten this into the idea of a divine monarch, but the Khmer conception is subtler and more durable. The devaraja is not the king’s ego raised to heaven; it is a protective presence, an incorporeal guarantor that binds sovereignty, land, and ritual into a single system. Kings rule not by personal divinity, but by correct alignment with this unseen centre.

In this moment, Cambodia is declared independent—not merely from a foreign overlord, but from fragmentation itself. The kingdom is no longer a patchwork of territories. It becomes Kambuja-desa: a land held together by shared ritual memory and an inherited axis of power.

Yet Jayavarman II does not remain on the mountain. Mahendraparvata is a place of declaration, not duration. Its rocky plateau resists water, agriculture, and growth. The king descends, carrying the ritual centre with him, and establishes his enduring capital at Hariharalaya, near present-day Roluos. Here, on fertile floodplain fed by the Tonle Sap and the rivers flowing from Kulen, the conditions of empire quietly assemble: rice, fish, labour, stone.

Temples rise, still modest by later Angkorian standards, but conceptually complete. The temple-mountain appears—an architectural echo of the act performed on Kulen. Stone now remembers what ritual first declared: that the world has a centre, and that centre can be built.

When Jayavarman II dies in 835, he is given the name Parameshwara—Supreme Lord—an epithet of Shiva. Yet his true legacy is not apotheosis. It is continuity. Every king who follows will draw legitimacy from the ritual current he established. Every tower, causeway, and baray will quietly assume that Cambodia is one body, oriented around a sacred core.

Angkor does not begin with splendour. It begins with measure.

Jayavarman II stands at the threshold where motion becomes structure. He does not rule from the heights of Angkor’s towers, but without him they would have no reason to rise. He is the mountain before the city—the moment when a scattered land learns again how to gather itself around silence, ritual, and stone.

Also in Library

The Spark and the Weight of Being Human

9 min read

At some point in our past, a human asked the first question—and self-awareness was born. Yet the same consciousness that gave us power also confronts us with our limits. This essay explores the paradox of being human: the spark of understanding and the weight of knowing.

The Pact of the Uncounted Grain

10 min read

A village does not starve only when rice runs out. It begins to thin when everything is counted, explained, and held too tightly. The Pact of the Uncounted Grain remembers an older law: that once each season, abundance must pass through human hands without measure, or the world begins, quietly, to lose its meaning.

A Manifesto for Modern Living

3 min read

The old certainties have weakened, yet the question remains: how should one live? This manifesto explores what it means to create meaning, think independently, and shape a life deliberately in an uncertain world.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap — reflections, field notes from the temples of Angkor, and glimpses into the writing and creative life behind the work.

When you subscribe, you will receive a complimentary digital copy of

Three Ways of Standing at Angkor — A Pilgrim’s Triptych, a short contemplative book on presence, attention, and the art of standing before sacred places.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet words, delivered gently.

Subscribe and step into the unfolding journey.