Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

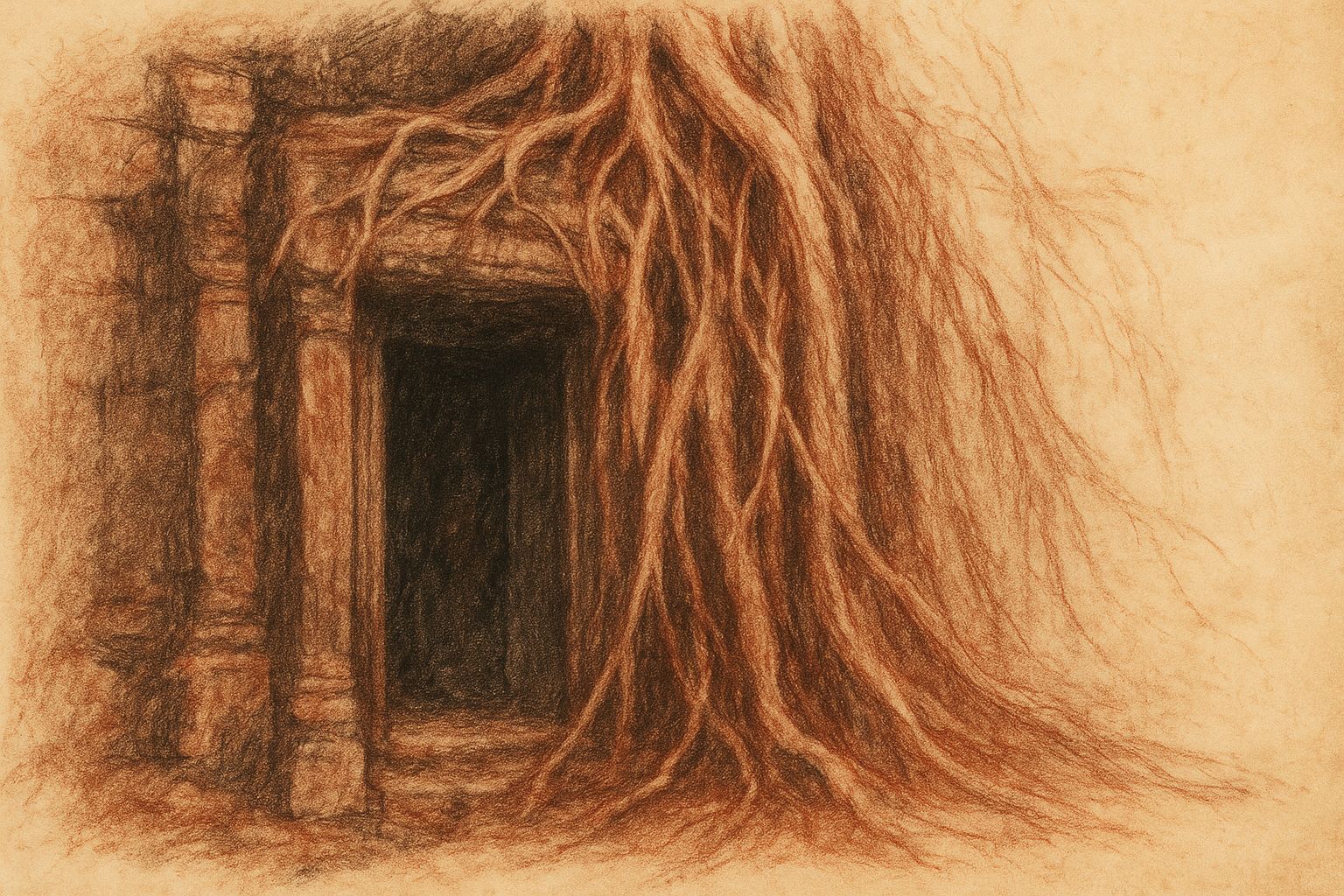

Roots Over Stone

3 min read

roots veil the doorway

stone breathes beneath their silence

light seeps like promise

The first sight is always a hush: roots suspended like ropes of time, thick with moss, lowering themselves over the gallery walls of Ta Prohm. They do not so much cover the temple as claim it, each tendril flowing into cracks, each trunk gripping a lintel as if tree and monument were joined in one slow embrace. A visitor arriving at dawn feels it immediately — the pull of two forces that seem opposed yet inseparable, stone built for permanence, roots moving only by centuries.

—

I stood before one of the great strangler figs, its pale trunk pressed against a tower wall. The stone beneath was split, yet it did not seem destroyed. Rather, it had become a vessel for another presence. The roots curled inward and outward, like ribs and veins, gestures of protection and conquest all at once. To touch the surface was to feel both the cool roughness of sandstone and the faint vibration of living sap. The temple breathed through the tree; the tree endured through the temple.

—

This is the hinge of Ta Prohm: the roots over stone are not accidents of neglect but the very image of survival.

The aftermath is inescapable. What appears as ruin is covenant. The tree cannot stand without the stone it grips; the stone cannot remain upright without the tree that binds it. We often come to monuments seeking permanence, but here we are taught that endurance is relational. Decay is not the enemy. It is the condition of continuity.

—

As I moved deeper into the galleries, the air cooled. Shadows pooled around collapsed corridors where roots trailed like ropes abandoned by pilgrims. Inscriptions flickered half-visible, letters fractured by tendrils yet still legible. The message seemed less about what words were carved than about how memory is carried forward through fracture. Roots do not erase; they translate. They take the weight of the wall and return it as living form.

I traced one fissure where a root had entered the joint between two stones. The gesture was intimate, as if a hand had slipped between clasped palms. Here was the talisman of the place: a crack inhabited, turned from weakness into bond. I found myself returning to it again and again, as though it held a secret words could not fully open.

—

Guides often speak of Ta Prohm as “nature reclaiming civilisation.” The phrase is repeated until it becomes cliché. But standing there, sketchbook damp against my hand, I understood the inadequacy of that formula. This is not reclamation but reciprocity. Civilisation built in stone. Nature answered in root. The dialogue is slow, uneven, and sometimes merciless, yet it is not war. It is conversation.

In one gallery, a devata’s face was almost hidden by a curving root. Only the outline of her cheek remained, her smile half-veiled. I sketched her as I saw her: stone dissolving into fibre, fibre tracing stone. The page blurred when drops of moisture fell. The drawing became a mirror of what I was witnessing — not clarity, but transformation.

—

Near midday, when the light grew sharper, I returned to the great fig at the entrance. Sun cut through the canopy and revealed how the bark shimmered against the sandstone blocks. The contrast was startling: pale trunk, dark stone. Yet the longer I looked, the less they seemed separate. Shadow braided them together, as if time itself had woven two elements into one fabric.

A bird lifted suddenly from the root, carrying in its wings a dust of pollen and grit. The movement startled me into remembering how fragile the balance is. Preservationists debate how much of Ta Prohm to restore, how much to leave to the jungle. Each choice carries cost: over-restoration risks sterility, neglect risks collapse. The root and the stone remind us that beauty often lies not in solving the tension but in living within it.

—

When I left, I paused at the threshold. The roots hung like curtains across the doorway, fibres swaying slightly in the wind. It felt less like an exit than a passage into another way of seeing. The opening promise — that hush of roots over stone — returned, altered. I no longer saw them as invasion. They were bond. They were testament.

The last thing I touched was the crack where root met wall. It was rough, damp, alive. That contact carried more weight than any photograph could. It was a reminder that endurance is not a matter of resisting time, but of embracing the slow entanglement by which stone and tree, silence and breath, past and present, hold one another in place.

Ta Prohm Temple

Beautiful museum quality archival prints on fine art paper depicting the ancient Ta Prohm Temple in the Angkor Archaeological Park in Cambodia.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.