Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

The Hell Without Rest: On the Avīci Realm at Angkor Wat

Even in darkness, the soul is not lost—only shaped.

The Heavens and Hells panel at Angkor Wat is more than a mural. It is a threshold.

Carved along the eastern wing of the southern gallery in the temple’s third enclosure, this monumental frieze stretches more than sixty-six metres in length. Weathered by centuries of monsoon light and temple breath, it reveals not only a vision of judgement and rebirth—but the Khmer imagination’s profound capacity for moral reckoning and sacred fear.

I stood for some time before the lower register, where the hells are carved. They are brutal, precise, and strangely beautiful in their allegory. This is not eternal condemnation—it is consequence. The sinners are weighed and sent downward—not for disbelief, but for deeds rooted in harm, desecration, or greed. And there, in the deepest recess of this sacred relief, one hell waits beneath all others.

It is called Avīci.

The hell without rest.

Flayed beneath the mountain’s weight,

the soul awakens too slowly—

but not forever.

Below the scenes of celestial judgement, the condemned tumble downward in sorrowful choreography. Some are dragged by the hair, others pierced by spears, bound to wheels, or cast into flame. Their gestures still echo the body’s last resistance, the soul’s cry in stone.

Sinners Cast Into Hell, Angkor Wat Temple, Cambodia

A celestial sentence falls—the judged are hurled downward, flayed, pierced, and silenced beneath the carvings of cosmic law.

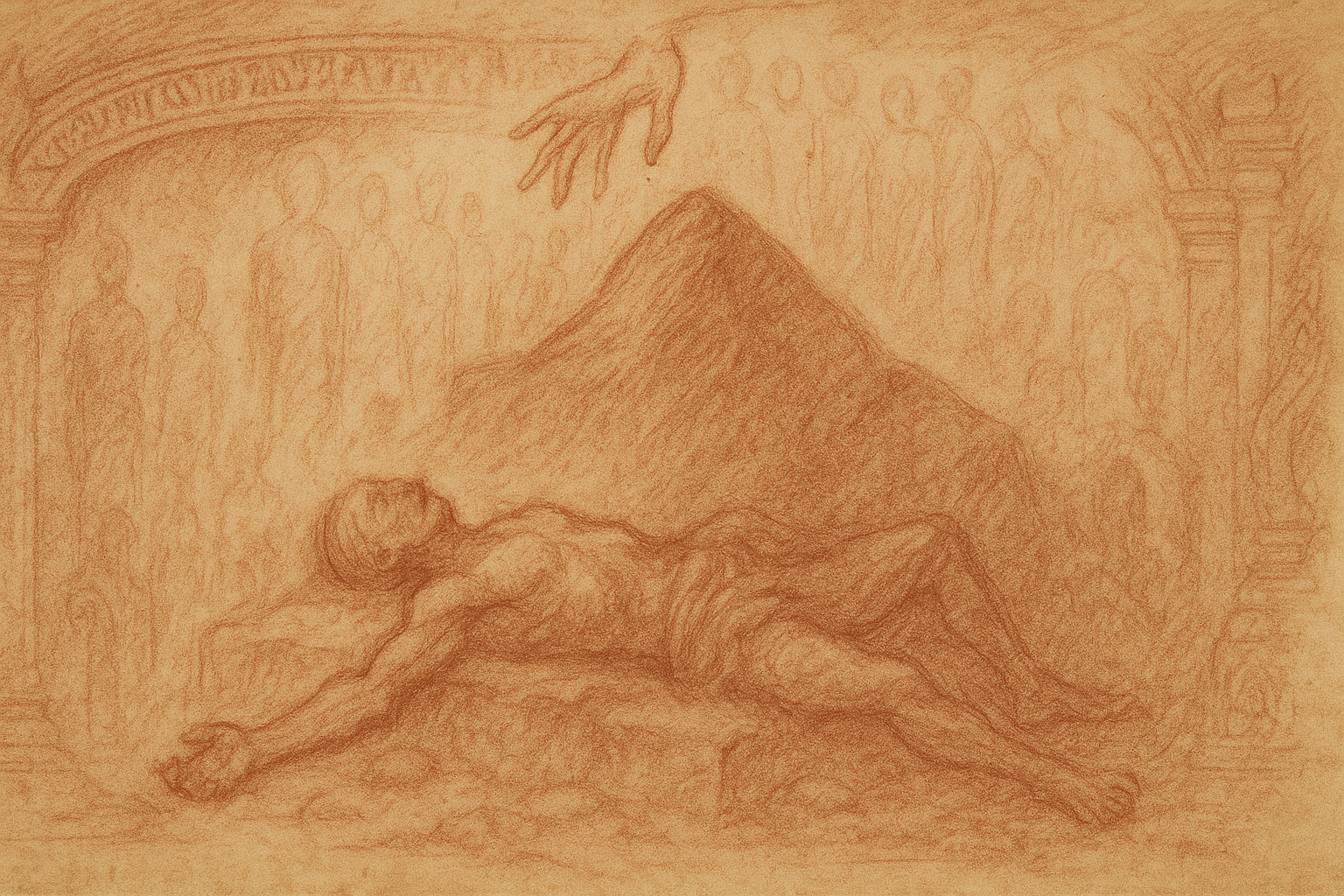

Among these figures, one lies stretched across a slab—his flesh scraped away with brutal tools. Around him, others lie buried beneath stone, crushed by the weight of a karmic mountain. No torment here is accidental. Every detail—every tool, gesture, chain—is charged with meaning.

Avīci, the lowest and most pitiless realm, receives those who “live in abundance and still live only in sin.” This is not punishment for ignorance, but for knowing and choosing otherwise—for betrayal of dharma in full daylight. A slow, relentless retribution unfolds in sculpted silence. And yet—even here—the Khmer vision whispers: hell is not eternal. It is purification.

Avīci Hell, Angkor Wat Temple, Cambodia

In the realm without rest, sinners lie buried beneath stone—those who had all, and still chose darkness.

Though many of the inscriptions were lost in the gallery collapse of 1947, a few survive—etched in fractured Sanskrit across the lintel above the underworld. They read like sacred fragments: sparse, weathered lines that still carry the weight of judgment.

Thirty-two hells are shown in total. This number aligns with Mahāyāna Buddhist cosmology, rather than the Hindu framework of seven, twenty-one, or twenty-eight. Even here, in a Vaishnava temple, Buddhist influence breathes through the stone. It is not contradiction, but communion. Khmer belief, in its deepest expression, is a fusion of Shaiva, Vaishnava, and Buddhist streams—braided together by centuries of prayer.

And yet, the punishments depicted are often Brahmanic in character. There is no mention of offences against the Buddha’s teachings, but many tortures for crimes against Shaivite law, the desecration of temples, or sacrilege against Brahmins. The severity is shocking—yet revealing. There is a hell for liars, another for vandals, another for those who relieve themselves in temple precincts. Even a specific hell exists for those who steal sandals.

To the modern eye, such sentences may seem theatrical. But they offer a mirror—not to theology, but to the values of Angkorean society. These were not abstract torments; they reflected the real transgressions of a sacred world. What the gods remembered, the stones recorded.

And yet, what is most striking is not the pain, but the impermanence.

Unlike Christian visions of eternal damnation, Hindu and Buddhist cosmologies see hell as temporary. A soul may descend into agony—but only so it may be reborn, cleansed. This is the fire that tempers gold, the chisel that reveals the figure within the stone. Avīci is the furthest descent, the final surrender—but never the end.

The punishments, vivid and elaborate, may have drawn from Khmer judicial practice or ritual theatre. But the sacred scrolls that once detailed these doctrines—likely kept in the libraries of Angkor—are lost. What remains is this carving, and a silence that speaks.

Centuries later, in fourteenth-century Sukhothai, King Luthai compiled the Trai Phum—the “Three Worlds.” It, too, speaks of thirty-two hells. Names are given, punishments described. The lineage may be uncertain, but the resonance is clear: a shared Southeast Asian imagination of sin, purification, and sacred reckoning.

And yet, to walk before these reliefs today is not to study doctrine. It is to encounter a memory carved in devotion. The anatomy is precise, the expressions alive, the composition filled with motion. But beneath all technique lies a quiet whisper: every act matters. Even those unseen. Even those forgotten.

This, perhaps, is the deeper meaning of Avīci—not its spectacle, but its promise.

Not its cruelty, but its call to awaken.

No soul is ever truly lost.

Only turned again, reshaped in fire,

awaiting light.

—

Beneath the crushing weight of stone, even the darkest soul is only sleeping.

Sanctum of Light and Stone

Photographs from Angkor Wat – Spirit of Angkor series by Lucas Varro

At Angkor Wat, the world is not only seen but felt—through corridors brushed by the breath of centuries, through carvings alive with myth and devotion. Built as a cosmic mandala in stone, this vast temple opens like a prayer, unfolding light across the faces of apsaras, warriors, and gods.

Within this sanctified geometry, artist Lucas Varro moves slowly, returning again and again with his large and medium format film cameras—not to document, but to listen. Each image in this collection was made at Angkor Wat and shaped through long exposure, chiaroscuro, and hand-toning, distilling not just what the temple looks like, but what it remembers.

These are photographs born in silence—etched in silver, shaded in reverence. A glance through shadow. A presence at the threshold. A single gesture of grace caught before it faded.

Offered as limited edition, hand-toned archival pigment prints on Hahnemühle Bamboo paper, each work is accompanied by a Collector’s Print Package including poetic writings, curatorial notes, and field reflections from the artist’s dawn pilgrimages.

This collection invites you to walk through Angkor Wat not with your eyes alone—but with your breath, your memory, and your spirit.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.