Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

The Quiet Reign — Jayavarman V and the Discipline of Unfinished Stone

There are kings who declare themselves in thunder, and others whose authority is learned in silence. Jayavarman V belongs to the latter. His reign does not announce a rupture or a conquest, but a long, measured holding of the centre—a period in which Angkor was neither refounded nor fractured, but patiently sustained.

He ascended the throne in 968 CE, not as a man formed by power, but as a child barely ten years of age. The empire he inherited from his father, Rajendravarman II, was stable, expansive, and confident in its Shaivite foundations. Yet stability at succession is not the same as security. For several years, the kingdom rested not in the hands of its boy-king, but in the guardianship of his tutor and regent, the Brahman Yajnavaraha.

This guardianship was not merely administrative. Yajnavaraha was granted the unprecedented title vrah guru—holy spiritual master—and with it, both religious legitimacy and political gravity. In his household, the young king was instructed not only in the Vedas and philosophy, but in medicine, astronomy, and the disciplined arts of seeing and measure. Court inscriptions suggest that this was no ceremonial tutelage. Jayavarman V was removed from the volatility of factional intrigue and placed instead within an architecture of care: protected, educated, and held.

The result is a reign curiously free of crisis. For nearly three decades, Angkor knew peace. No major wars fracture the record. No radical reorientation of cult or capital interrupts the flow. Instead, the kingdom consolidates—economically, intellectually, and artistically. It is in this climate that one of the most refined monuments of the Khmer world is conceived: Banteay Srei, founded not by the king himself, but by his guru. Small in scale yet astonishing in precision, the temple stands as an emblem of the age: an assertion that mastery does not require monumentality, only attention.

And yet, Jayavarman V is not remembered for delicacy alone. Toward the end of his reign, he initiates a project of formidable ambition—the temple now known as Ta Keo. Its original name, Hemasringagiri—the Mountain with Golden Peaks—announces a vision of Mount Meru rendered in stone, rising sheer and unornamented from the plain. It was to be the centrepiece of a new royal foundation, Jayendranagari, on the western edge of the East Baray.

But Ta Keo was never finished.

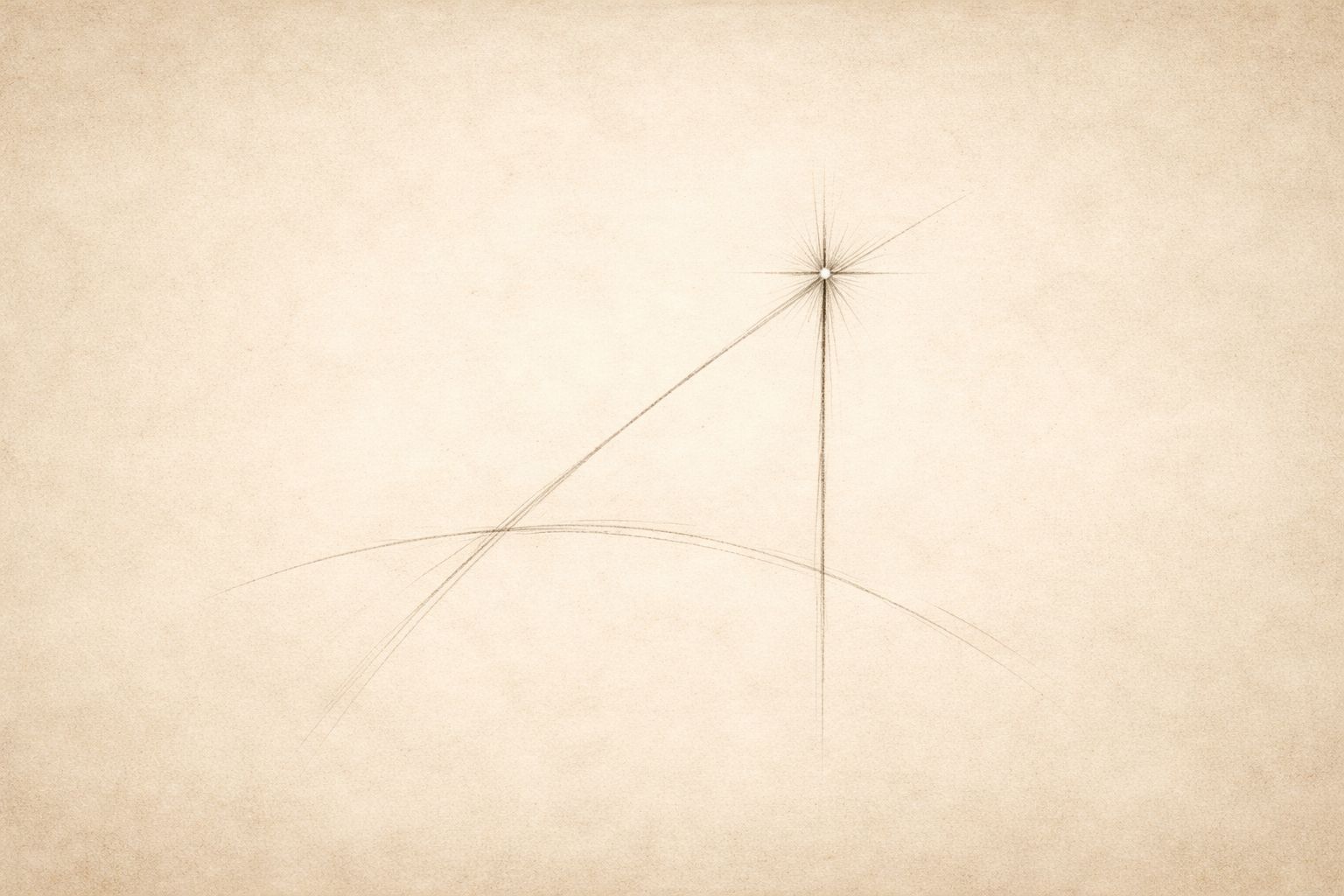

Its walls remain largely undecorated. Doorways stand without relief. The mass ascends in disciplined geometry, yet stops short of completion, as if arrested mid-thought. Later tradition speaks of lightning striking the sanctuary—an inauspicious omen—but history suggests something quieter and more human: the death of the king in 1001 CE, followed by a decade of contested succession that left no one able, or willing, to complete another man’s mountain.

Jayavarman V received the posthumous name Paramaviraloka—he who has gone to the supreme heroic world. Yet his legacy is not heroic in the usual sense. It is defined instead by continuity without climax, ambition without resolution, authority exercised through restraint rather than display. His reign demonstrates that Angkor was not only shaped by founders and reformers, but also by stewards—those who held the centre long enough for refinement to occur.

Ta Keo remains as his most eloquent testament. A golden mountain that was never gilded. A Meru left intentionally bare, or perhaps simply left alone. In its unfinished stone, one feels the character of the reign itself: measured, stable, and vulnerable to the quiet truth that even the most disciplined order depends on time being kind.

When the dynasty faltered after his death, it was not because Jayavarman V failed to build forcefully enough, but because he built in trust—trust that continuity would endure. For a generation, it did. And that, in Angkor, is no small achievement.

Also in Library

The Spark and the Weight of Being Human

9 min read

At some point in our past, a human asked the first question—and self-awareness was born. Yet the same consciousness that gave us power also confronts us with our limits. This essay explores the paradox of being human: the spark of understanding and the weight of knowing.

The Pact of the Uncounted Grain

10 min read

A village does not starve only when rice runs out. It begins to thin when everything is counted, explained, and held too tightly. The Pact of the Uncounted Grain remembers an older law: that once each season, abundance must pass through human hands without measure, or the world begins, quietly, to lose its meaning.

A Manifesto for Modern Living

3 min read

The old certainties have weakened, yet the question remains: how should one live? This manifesto explores what it means to create meaning, think independently, and shape a life deliberately in an uncertain world.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap — reflections, field notes from the temples of Angkor, and glimpses into the writing and creative life behind the work.

When you subscribe, you will receive a complimentary digital copy of

Three Ways of Standing at Angkor — A Pilgrim’s Triptych, a short contemplative book on presence, attention, and the art of standing before sacred places.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet words, delivered gently.

Subscribe and step into the unfolding journey.