Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

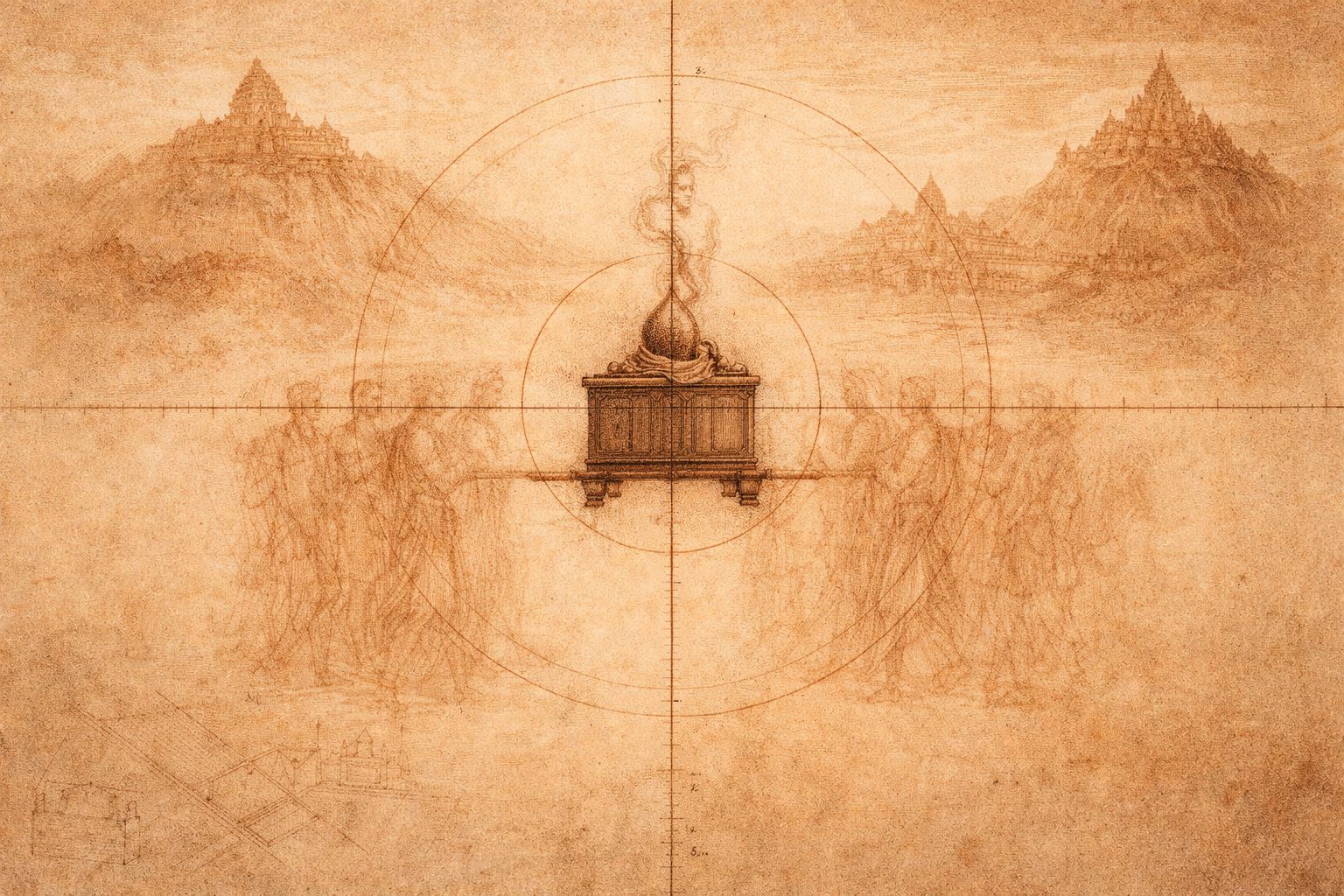

Devarāja — The Axis That Does Not Move

3 min read

The word devarāja is often translated too quickly.

“God-king,” it is said—an image that invites excess: crowns raised to heaven, rulers mistaking themselves for gods. But the Khmer conception is quieter, and far more durable. The devarāja is not a man elevated. It is a centre installed.

In the early ninth century, Cambodia was not yet a body. Power existed in fragments—local lords, itinerant courts, loyalties tied to land rather than lineage. Authority moved, but it did not yet hold. When Jayavarman II ascended, what he confronted was not merely political disorder, but the absence of a shared axis. There was no single point around which the realm could remember itself.

The response was not conquest alone. It was consecration.

In 802 CE, on the sandstone plateau of Phnom Kulen—ancient Mahendraparvata, the Mountain of Indra—Jayavarman II enacted a ritual that was as precise as any act of engineering. Assisted by the Brahmin Hiranyadama, he established the devarāja: kamrateṅ jagat ta rāja, “the god who is king.” Not the king as god, but the god as sovereign presence—an incorporeal guarantor binding land, ritual, and rule into a single system.

This was a declaration of independence, but not only from a foreign suzerain named “Java.” It was independence from dispersion itself. Cambodia would no longer be a collection of territories. It would become Kambuja-desa: a land oriented around a sacred centre that did not belong to any one place, yet sanctified every place it touched.

The devarāja was not fixed. That is its crucial distinction. Unlike the great lingas of India, rooted permanently in stone sanctuaries, the Khmer devarāja moved. It travelled with the king. Wherever the “Lord of the Earth” established his court, the devarāja was installed anew, ensuring continuity across shifting capitals. Authority could relocate without dissolving, because the axis remained intact.

Modern scholarship has wrestled with the nature of this presence. Early interpretations imagined the king’s subtle self residing within a royal linga. Later readings suggest something more restrained: Shiva himself, sovereign of the gods, acting as a protective counterpart to the mortal ruler. What matters is not the object—whether stone, flame, or image—but the function. The devarāja was the empire’s palladium: the unseen condition that made rule legitimate.

Our knowledge of the cult comes primarily from the Sdok Kak Thom inscription, carved in the eleventh century by a priestly family charged with its guardianship. Their account does not speak in mythic excess. It records rights, lineages, recitations. The ritual was technical. It required precision. Four Sanskrit texts—Vinashikha, Sirascheda, Sammohana, Nayottara—were recited and transmitted, collectively called “the four faces of Tumburu.” These were not hymns of praise, but operative knowledge: a tantric grammar through which sovereignty could be correctly installed.

To modern eyes, this can feel abstract. But its effects are visible everywhere in Angkor.

The temple-mountain rises where the devarāja once stood. The capital aligns itself around a centre that does not belong to the king’s body, but to the realm itself. Every causeway assumes an axis. Every baray presumes order. Stone remembers what ritual first declared.

When the state later turned toward Mahayana Buddhism under Jayavarman VII, the system was not abolished. It was translated. The devarāja became the buddharāja. The axis remained; the theology shifted. Only with the spread of Theravada Buddhism—sceptical of aristocratic divinity—did the cult finally dissolve. Yet even then, the architecture continued to speak its language of centre and measure.

The devarāja was never spectacle. It did not demand belief in a divine king. It demanded fidelity to alignment.

If Angkor endures, it is because its founders understood something rare: that power cannot rely on personality alone. It must be housed in something quieter, something that does not move when rulers do. The devarāja was that stillness—the fixed point around which a civilisation learned to stand.

Also in Library

The Devata at First Light

8 min read

At first light in Banteay Kdei, a devata draws the eye into stillness. Through sanguine chalk, black shadow, and repeated returns to the page, sketch and prose slowly deepen into a single act of devotion—until the words, too, learn how to remain.

The Spark and the Weight of Being Human

9 min read

At some point in our past, a human asked the first question—and self-awareness was born. Yet the same consciousness that gave us power also confronts us with our limits. This essay explores the paradox of being human: the spark of understanding and the weight of knowing.

The Pact of the Uncounted Grain

10 min read

A village does not starve only when rice runs out. It begins to thin when everything is counted, explained, and held too tightly. The Pact of the Uncounted Grain remembers an older law: that once each season, abundance must pass through human hands without measure, or the world begins, quietly, to lose its meaning.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap — reflections, field notes from the temples of Angkor, and glimpses into the writing and creative life behind the work.

When you subscribe, you will receive a complimentary digital copy of

Three Ways of Standing at Angkor — A Pilgrim’s Triptych, a short contemplative book on presence, attention, and the art of standing before sacred places.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet words, delivered gently.

Subscribe and step into the unfolding journey.