Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Jayavarman IV — The King Who Built Away from Memory

3 min read

Some kings consolidate.

Others inherit.

A few, very rarely, walk away.

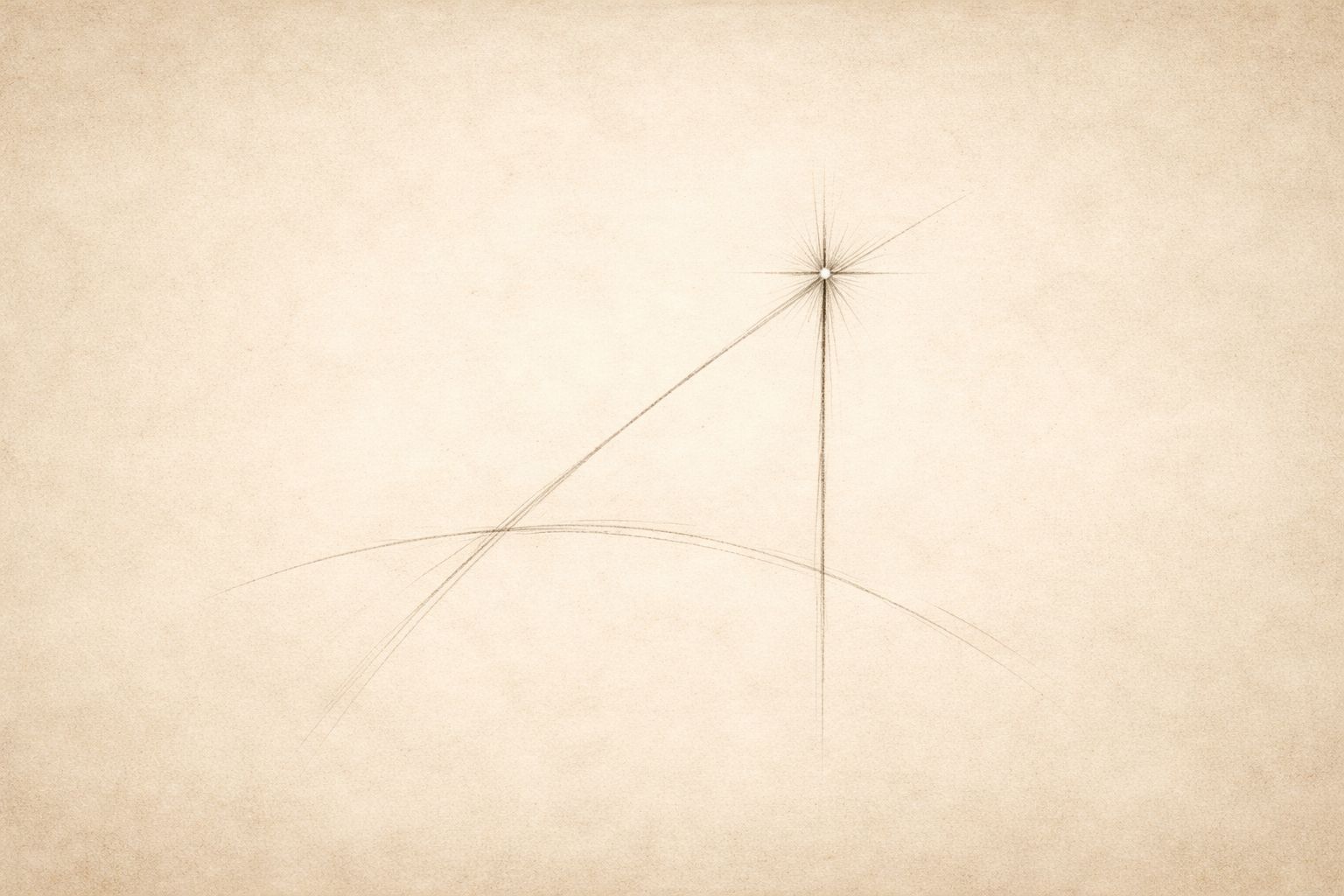

Jayavarman IV belongs to that smaller and more unsettling category: the ruler who refused the gravitational pull of Angkor and instead tested whether kingship itself could survive dislocation. His reign does not unfold along the causeways of precedent but cuts a hard diagonal across Khmer history, carving a capital out of forest, rock, and will at Koh Ker.

To understand him, one must resist the easy language of usurpation or ambition alone. Koh Ker was not merely a rival city. It was an argument.

When Jayavarman IV left Yashodharapura around 921 CE, Angkor was already dense with memory—temples accreted like sediment, authority layered through repetition. He did not dismantle this inheritance. He stepped outside it. From his own territorial base he began constructing a capital that did not ask permission from the past, only obedience from the present.

The sources tell us he was a maternal uncle to the reigning line, married into royal legitimacy, close enough to power to feel its pulse yet far enough to imagine its re-engineering. For several years he ruled as a king in waiting, a sovereign without consensus. Then, after the death of Ishanavarman II, the inscriptions shift. Jayavarman IV is named cakravartin—not first among equals, but universal monarch.

The question is not whether he seized power. The question is how he defined it.

At Koh Ker, kingship abandoned delicacy. The temples are not measured whispers but blunt declarations. Prasat Thom rises in seven stepped tiers, a sandstone pyramid that does not conceal its mass or temper its scale. This is architecture that advances rather than invites. It does not court the eye; it confronts it.

At its summit once stood a colossal liṅga—too large to be symbolic alone. Here, the divine was not implied. It was imposed. Jayavarman IV’s chosen form of Shiva, Tribhuvaneshvara, was not merely the god of three worlds but the god who was lordship itself. In the language of the inscriptions, divinity and sovereignty collapse into a single term. The king does not serve the god. The god is the condition of kingship.

This is why Koh Ker feels so different from Angkor. The art surges with movement—wrestlers locked in strain, ape kings frozen mid-combat, Shiva captured not in repose but in centrifugal force. Scale becomes rhetoric. Motion becomes proof.

Even water submits to this logic. The Rahal Baray is not gently contained but partially hewn from bedrock, an act of extraction as much as engineering. Nature is not aligned; it is compelled.

And yet, for all this ferocity, Jayavarman IV was not a doctrinaire ruler. He endowed distant sanctuaries such as Wat Phu, and through his officials supported Buddhist foundations at Angkor itself. Koh Ker was not a theological break, but a political one. Shiva remained central, but the field of devotion stayed plural.

His reign burned bright and fast. He died in 941 or 942 CE, entering posthumous union with Shiva. His son reigned briefly. Then the court returned to Angkor, drawn back by memory, water, and habit. Koh Ker was left suspended—complete yet abandoned, an answered question no one wished to repeat.

Jayavarman IV teaches us something uncomfortable: that power can be re-founded, but only briefly; that scale can persuade, but not endure; that kingship untethered from inherited place must shout to be heard.

Koh Ker remains his voice.

It has not softened with time.

It waits, still asking whether authority is something we inherit—or something we dare to build alone.

Also in Library

The Spark and the Weight of Being Human

9 min read

At some point in our past, a human asked the first question—and self-awareness was born. Yet the same consciousness that gave us power also confronts us with our limits. This essay explores the paradox of being human: the spark of understanding and the weight of knowing.

The Pact of the Uncounted Grain

10 min read

A village does not starve only when rice runs out. It begins to thin when everything is counted, explained, and held too tightly. The Pact of the Uncounted Grain remembers an older law: that once each season, abundance must pass through human hands without measure, or the world begins, quietly, to lose its meaning.

A Manifesto for Modern Living

3 min read

The old certainties have weakened, yet the question remains: how should one live? This manifesto explores what it means to create meaning, think independently, and shape a life deliberately in an uncertain world.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap — reflections, field notes from the temples of Angkor, and glimpses into the writing and creative life behind the work.

When you subscribe, you will receive a complimentary digital copy of

Three Ways of Standing at Angkor — A Pilgrim’s Triptych, a short contemplative book on presence, attention, and the art of standing before sacred places.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet words, delivered gently.

Subscribe and step into the unfolding journey.