Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Multiplicity and Mercy — The Face Towers of Jayavarman VII

First light gathers around the Bayon in quiet stages. The temple’s upper towers emerge from the soft blue of morning, their contours resolving as the sky brightens. From a distance the peaks appear like clustered pinnacles; only when one draws near do the great faces reveal themselves — calm, steady, and turned toward every horizon. Their presence is unmistakable yet never abrupt. The temple seems composed not only of stone but of watchfulness.

These towers are the most visible expression of a new political and religious imagination taking shape in Jayavarman VII’s reign. Inscriptions from Prah Khan, Ta Prohm, and the network of rest houses and hospitals describe a ruler who “felt the pains of his subjects as his own,” a king who understood sovereignty as ethical responsibility rather than inherited privilege. Infrastructure becomes moral action: roads to ease travel, bridges to maintain connection, shelters for weary pilgrims, medical foundations for the ill. Care is not an abstract virtue but a policy inscribed into the land.

The faces at the Bayon belong to this moral landscape. Their features echo Avalokiteshvara — lowered lids, rounded contours, a gentle, inward composure — yet their proportions also recall royal portraits. The ambiguity is not a flaw but a deliberate theological position: the king embodies the bodhisattva ideal not through deification but through conduct. By multiplying the serene face across the city and countryside, Jayavarman’s administration projects an image of guardianship. The ruler becomes a steady presence oriented to all directions, attentive to suffering wherever it appears.

This theme of direction is crucial. In Khmer architecture, orientation shapes meaning: gopuras mark thresholds; cardinal points organise space; the temple’s axes mirror cosmic order. Under Jayavarman VII, this system is expanded dramatically. At Angkor Thom, each city gate bears four faces looking outward to the quarters. At the Bayon, dozens of towers repeat the pattern. Direction is no longer only spatial; it becomes visionary. The four quarters, significant in Indic cosmology as living horizons guarded by deities, now receive a humanised but contemplative presence. The city functions as a mandala whose centre is carried upward through the mesh of towers, aligning earthly and cosmic sight.

The Bayon expresses this vision through a spatial experience unique in Angkor. The towers are not arranged in perfect symmetry; instead, they form a shifting constellation. As one moves through the terraces, faces appear, align, separate, and reappear. A tower glimpsed head-on a moment earlier may dissolve into profile with a few steps. Two distant towers may suddenly align to form a pair of matching visages, only to drift apart as one rounds a gallery corner. This continual reconfiguration means that the visitor never encounters a single, fixed composition. One moves through a field of presence rather than a set of discrete images.

This atmosphere distinguishes the Bayon sharply from earlier monumental programmes. Angkor Wat relies on narrative panels to express cosmic drama: creation myths, historic battles, celestial processions. The Bayon abandons narrative on its upper levels. Instead of scenes, it offers states of being. One expression, repeated many times, suffuses the space with a singular mood. Multiplicity does not dilute meaning; it concentrates it. The pilgrim, rather than responding to a story inscribed in relief, is drawn into an environment structured by calm attention.

Light plays a decisive role in shaping this environment. The upper terraces are arranged so that towers catch and release illumination throughout the day. Morning reveals crisp contours; midday flattens surfaces into brightness; late afternoon draws faces into shadow where only the curve of a cheek or the arc of lips remains visible. The faces are encountered not as static icons but as elements that participate in the rhythms of light. Their visibility fluctuates, encouraging the visitor to look, adjust, and look again. Interpretation becomes an act of attention.

Time itself has softened these towers. Weathering has rounded eyelids, smoothed lips, and reduced sharp detailing, creating expressions that feel more contemplative than the original sculptors could have predicted. From below, erosion reads as gentleness, not loss. In their present state, the faces hold two truths at once: the compassion they were designed to convey and the impermanence that centuries have added. The towers witness the passing of time without resisting it, reinforcing a worldview in which endurance is shaped by change.

Craft underpins this entire achievement. The towers were built block by block into tall, hollow structures held together by precise stone fitting rather than mortar. Only when the architecture stood complete did sculptors carve the faces into the tower mass. This method allows the sculpture to arise organically from structure. The faces are not attached ornaments; they emerge from the architecture itself. Many stones form one tower; one tower becomes one face. The principle mirrors the philosophical message: unity arising from multiplicity.

The scale of coordination is noteworthy. Dozens of teams seem to have worked on different towers, yet the coherence of physiognomy is remarkable. Eyes, lips, cheeks, and contours follow consistent proportions. Features are simplified and slightly enlarged to remain legible at distance. This harmony suggests master models, shared training, and careful supervision. Angkor often displays architectural grandeur; here, it shows an equally formidable unity of artistic intent.

The motif did not appear everywhere, and the selectivity is telling. Preah Khan, despite belonging to the same compassionate programme, remains without face towers. Banteay Chmar and remote shrines integrate smaller versions, though sometimes in irregular placement. The distribution communicates a hierarchy of meaning: not all spaces required or warranted the charged symbolism of the serene face. Where the motif appears, it marks a place where political and spiritual identity are explicitly intertwined.

History confirms the motif’s potency. During the anti-Buddhist reaction that followed Jayavarman VII, it was these faces that suffered the most targeted damage: eyes chipped away, mouths defaced, entire visages recut into other forms. Their destruction was not incidental but ideological. To remove the face was to dismantle the vision of kingship it represented — a reminder that these towers were never neutral elements but explicit statements of value.

Comparative traditions help contextualise the Bayon within a broader Indic world. Four-faced deities such as Brahma, directional guardians, and multiform divine aspects all contribute possible resonances. The meditative expression echoes Avalokiteshvara; the physiognomy echoes the king; the monumental scale recalls cosmic guardianship. Sanctuary analysis does not reduce these layers to a single identification. Instead, the Bayon is understood as a deliberate synthesis: an architectural expression of a worldview in which human authority aligns with cosmic order and compassionate principle.

Within Angkor’s intertwined religious landscape — where Hindu and Buddhist forms repeatedly overlap — the face towers represent a refined articulation of syncretism. They do not merge traditions indiscriminately; they integrate them with clarity. A single serene face at every horizon crystallises Jayavarman VII’s reimagining of kingship and cosmic alignment: a kingdom anchored by steady regard, a cosmology expressed in human terms, and a devotional ideal made visible at monumental scale.

To enter this space is to recognise that the Bayon does not teach through inscription or narrative. It teaches through organisation, orientation, and atmosphere. The pilgrim walks not simply between towers, but within a field of compassionate vigilance. One is not asked to enact devotion; one is invited to notice what it feels like to be seen with steadiness and without judgement.

Under Jayavarman VII, the civilisation shaped an ethic into architecture. By lifting a serene face to every horizon, Angkor articulated a vision in which kingship becomes guardianship, cosmos becomes ordered attention, and compassion becomes the climate through which one moves.

Also in Library

From Mountain to Monastery

2 min read

Angkor Wat survived by learning to change its posture. Built as a summit for gods and kings, it became a place of dwelling for monks and pilgrims. As belief shifted from ascent to practice, stone yielded to routine—and the mountain learned how to remain inhabited.

Why Theravada Could Outlast Stone

2 min read

Theravada endured by refusing monumentality. It shifted belief from stone to practice, from kings to villages, from permanence to repetition. What it preserved was not form but rhythm—robes, bowls, chants, and lives lived close together—allowing faith to travel when capitals fell and temples emptied.

The End of Sanskrit at Angkor

2 min read

The final Sanskrit inscription at Angkor does not announce an ending. It simply speaks once more, with elegance and certainty, into a world that had begun to listen differently. Its silence afterward marks not collapse, but a quiet transfer of meaning—from stone and proclamation to practice, breath, and impermanence.

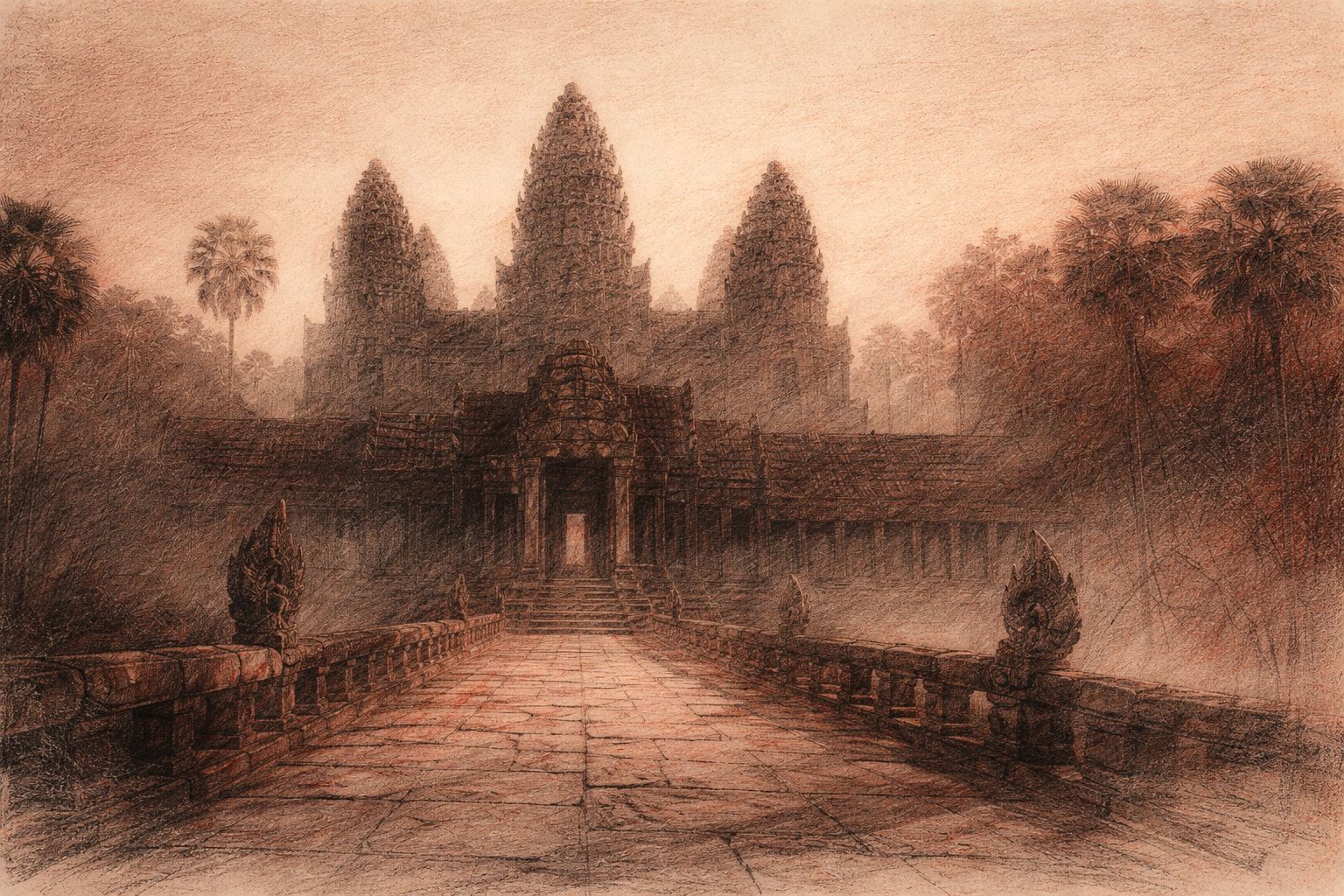

Bayon Temple, Angkor, Cambodia — 2018

Limited Edition Archival Pigment Print

Edition

Strictly limited to 25 prints + 2 Artist’s Proofs

Medium

Hand-toned black-and-white archival pigment print on Hahnemühle Bamboo — a museum-grade fine art paper chosen for its quiet tactility and reverent depth, echoing the spirit of the temples.

Signature & Numbering

Each print is individually signed and numbered by the artist on the border (recto)

Certificate of Authenticity

Accompanies every print

Image Size

8 x 8 inches (20.3 x 20.3 cm)

Dawn gathers in Bayon’s corridors like water in a stone bowl, cool and unhurried. Two faces emerge—one cloaked in the last breath of night, the other brushed by the first silver syllable of morning. Their exchange seems less carving than thought made visible.

In this suspended hush, centuries contract to the width of a heartbeat. The terrace beneath me belongs to no empire, only to presence: stone inhaling light, exhaling stillness.

I pressed the shutter only when my breathing matched the temple’s. Medium-format black-and-white film accepted the moment’s slow cadence; in the darkroom I polished shadow and glow as one turns prayer beads, until compassion stirred within the grains. Hand-toning followed, gifting each print its own quiet pulse.

This strictly limited edition of twenty-five prints (with two Artist’s Proofs) rests on Hahnemühle Bamboo paper whose warm fibers cradle silver and carbon like earth cradles seed. Signed, numbered, and accompanied by a certificate of authenticity, each piece is a silent threshold of reflection.

May it find the wall where your own silence waits.

To walk deeper into the hush behind this image, click here to enter the Artist’s Journal.

Previously titled ‘Face Towers I, Bayon Temple, Angkor, Cambodia. 2018,’ this photograph has been renamed to better reflect its place in the series and its spiritual tone. The edition, provenance, and authenticity remain unchanged.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.