Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Awe Without Make-Believe

11 min read

A spiritual essay against Woo

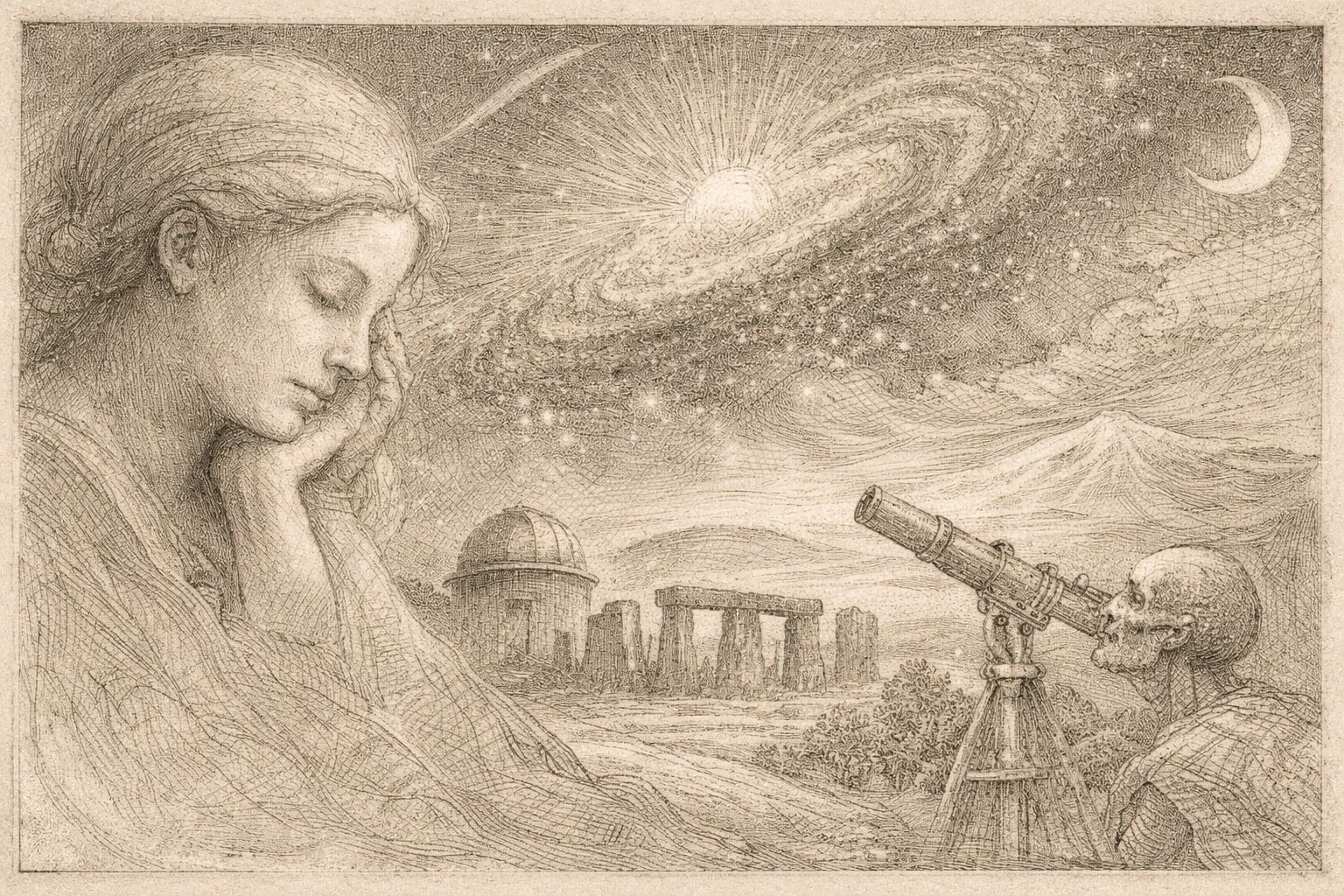

There are nights when the universe does not merely appear vast, but intimate — as if magnitude itself leans down and presses its forehead to yours.

The sky is clear. The air is still. Stars do not twinkle with romance; they burn with indifferent precision. The mind reaches for names. Wonder. Reverence. Gratitude. A kind of holy fear. But language was not built for this. It buckles. And one begins to understand why human beings invented gods: not only from ignorance, but from contact — from the shock of being alive inside something so immense it does not need you, yet holds you anyway.

I have had those nights. In wilderness. In cities. In the presence of stone older than my culture’s most ambitious dreams. I have had them alone and I have had them in grief. I have had them when joy arrived without warning like a stranger’s warm hand on the shoulder. I have had them when beauty in the world was so clean, so excessive, it felt almost indecent — the way light can be, the way water can be, the way a face can be when you suddenly see it as if for the first time.

If someone asked whether I consider myself spiritual, I would not hesitate.

But if they asked whether I believe in the supernatural, I would answer with equal clarity: no.

Not because I am closed. Not because I am afraid. Not because I cannot feel what others claim to feel. But because I have no use for pretending that reverence requires falsehood — and no patience for the idea that our ignorance gives us licence to fabricate.

There is a difference between mystery and make-believe. Between awe and assertion. Between the sacred and the invented.

And it matters now more than ever.

A strange sickness has spread — not only in fringe communities, but in the bloodstream of the culture — in which “spirituality” increasingly means: believe whatever comforts you. Accept whatever flatters you. Call it true because it feels warm in the mouth. Call it wisdom because it sounds ancient. Call it healing because someone said it with conviction. And if anyone raises an eyebrow, accuse them of being rigid, negative, “scientistic,” or worst of all: closed minded.

This is not openness. It is surrender. It is not insight. It is indulgence.

What is casually called “woo-woo” I will call Woo — because it is not harmless.

Woo is the conversion of mystery into licence: belief without warrant, certainty without evidence, and comfort sold as cosmology. It is the casual corruption of truth. The monetisation of wonder. The transformation of uncertainty into a marketplace.

The Woo merchant does not stand under the night sky and fall silent. They stand there and sell you an answer.

The answer is always convenient. Always positioned beyond verification. Always friendly to the ego. It makes the believer feel chosen: more attuned, more awake, appointed by the universe.

Here is where the line must be drawn — not out of bitterness, but out of love. Because I love the sacred too much to let it be hijacked by fantasy dressed up as depth.

The discipline of science shaped me early. Not in the shallow sense of collecting facts, but in the deeper sense of learning posture: how to approach the unknown with sobriety; how to distinguish what one wishes from what one can legitimately claim; how to love mystery without exploiting it.

A true scientist is not someone who has answers. It is someone who has restraints. And among those restraints the most beautiful is a simple phrase: we don’t know for sure.

When said sincerely, it is not weakness. It is strength. It is integrity. It means: I will not fill the gap with theatre. I will not dress ignorance in costume. I will not turn my own longing into an instrument of knowledge. I will not falsify the speech of reality.

People misunderstand this. They hear “we don’t know for sure” and interpret it as a void — a blank permission slip to invent. They assume humility is the same as laxity.

But humility is not laxity. Humility is structure. It is the spine of real openness. The truly open mind is not the mind that accepts anything. It is the mind that keeps its doors unlocked and still checks what enters.

If you care about truth, you do not step past uncertainty and begin speaking with the voice of a prophet.

You step past it and become more careful.

Woo does the opposite. Woo treats “we don’t know” as a resource. A gap to exploit. A fertile soil for certainty, charisma, and commerce.

This is not a harmless aesthetic problem. It has consequences. It erodes epistemic hygiene — the ability of a person, a culture, a civilisation, to tell the difference between what is supported and what is merely claimed. It teaches the mind to stop washing its hands. And once that hygiene collapses, anything can be smuggled in wearing the clothing of insight.

I have watched intelligent people — good people — be seduced by it.

Often they begin in sincerity. They are weary of sterile materialism. They are hungry for meaning. They have been hurt. They have lost something. They feel, correctly, that their inner life is larger than what their culture knows how to validate. They want a language for soul without church. Reverence without doctrine. Depth without sermon.

I understand this completely.

But understanding is not endorsement.

Because the moment a person becomes vulnerable, Woo appears like a healer in a robe, offering a narrative that makes the pain meaningful and the self central. It offers invisible forces that can be managed. It offers secret knowledge. It offers relief from uncertainty.

And it offers the most seductive drug of all: exemption from ambiguity.

Ambiguity is hard. The unknown is hard. Real spiritual honesty is hard.

In illness, for instance, it is hard to look at suffering and admit that it might not have a message. That it might not be punishment. That it might not be a lesson. That it might not be cosmically orchestrated for growth.

When someone you love is sick — the antiseptic sting in the air, the IV bag ticking empty, the monitor insisting on its green line — the mind burns for an answer. It wants a reason. It wants to believe that the world is a moral machine and that every affliction has a corresponding metaphysical cause. It wants to think: if we find the spiritual key, we can unlock the cure. We can negotiate with the invisible.

Woo whispers: yes.

It whispers that disease is a vibration mismatch. A blockage. A failure of alignment. Trauma stored in cellular memory. It whispers that the right ritual, the right crystal, the right energetic practitioner, the right “frequency medicine” will restore order.

In its cruelest form it whispers something worse: that the sick person has invited their illness through negativity; that they are choosing it on some level; that they are failing to heal because they are failing spiritually.

Here the game becomes harm.

Because illness is not primarily a philosophical problem. It is a biological and human problem. It lives in tissue. It costs energy. It consumes time. It devours futures. It hurts.

And the sick person’s need is not metaphysical blame disguised as empowerment. Their need is care. Tenderness. Good medicine. Clear thinking. A spiritual companion who is not using them as a stage for certainty.

The purest spiritual act I have ever witnessed in illness was not a miracle claim. It was a hand held quietly at two in the morning. It was a glass of water offered without comment. It was the refusal to turn suffering into a sermon.

Grief is where this becomes unbearable.

Grief shatters the illusion that life can be managed by planning. It breaks time. It makes the future feel like a room with the furniture removed. It creates moments when metaphysics seems not only plausible but necessary — because the longing for contact becomes unbearable. You want a sign. You want evidence that the bond did not end. You want to believe death is porous.

The toothbrush still stands by the sink, untouched, as if waiting for a hand that will never return.

And again Woo arrives, tender as a salesperson: they are still here. They are speaking to you. That bird. That breeze. That flicker of light. That number on the clock. That dream. That coincidence.

Some of it may even feel true.

The psyche is powerful. Love is powerful. The mind in grief searches for continuity the way roots search for water. It will attach meaning to what it touches. This is not stupidity. It is devotion.

The question is what we do with devotion.

Do we honour it by accompanying it honestly — by saying, yes, love continues: in memory, in consequence, in the way your body has been shaped by another’s presence?

Or do we exploit it by claiming invisible communications that cannot be tested and cannot be challenged?

There is a difference between poetry and pretence.

It is one thing to speak with reverence: to say that the dead remain with us in ways we cannot fully name. That the bond is not erased by absence. That the world still carries their trace.

It is another thing to turn that trace into literal metaphysics — to claim knowledge of what happens after death; to interpret signs; to speak on behalf of the departed.

People ask: why does it matter, if it comforts them?

It matters because comfort purchased with falsity is unstable. It becomes dependency. It becomes a kind of addiction to reassurance. It erodes something precious: the ability to stand in reality without bribing oneself.

I have known people who lived in a constant interpretive frenzy, endlessly scanning the world for signs and synchronicities, unable to sit with ordinary silence. Their spirituality became not a deepening but an agitation. Not reverence, but paranoia disguised as meaning.

Behind it always lurked fear: if the signs stop, what then?

The deepest spiritual maturity I have ever seen in grief does not look like certainty. It looks like sorrow carried with dignity. It looks like the willingness to miss someone without claiming them. It looks like the courage to love without metaphysical guarantees.

“Where are they now?” is not always a question that can be answered.

Sometimes the truest answer is: I don’t know for sure.

And sometimes that answer, spoken gently, becomes a kind of prayer — not to a god, but to truth itself.

After grief, the hunger for meaning does not disappear. It merely changes costume.

As an artist, I understand the temptation from inside. Art touches depths that ordinary language cannot. It can feel as if something larger than the self moves through the hands. The work has its own logic. The piece instructs the maker.

But to honour this does not require supernatural claims. There is a difference between reverence and theatre: between admitting mystery and claiming authority. An artist who says, I don’t know where it comes from, but something comes, honours the unknown. An artist who says, I channel cosmic beings, turns the unknown into a stage — and invites followers.

The world currently contains too many people claiming spiritual authority without accountability, without evidential obligation, without humility. Too many prophets selling certainty in exchange for attention.

This is why I push back.

Not because I want to strip the world of beauty.

Because I want to protect beauty from corrosion.

Wonder is fragile. Reverence is fragile. The sublime is fragile — not because it is weak, but because it is easy to counterfeit.

Woo counterfeits the sacred by making it easy, legible, purchasable.

Real awe is not easy. It is often disorienting. It can even be frightening, because it reveals how little control we have. It reveals the scale of time, the indifference of nature, the contingency of our lives.

Woo cannot tolerate this.

Woo softens the sublime into something emotionally manageable. It domesticates mystery. It puts a leash on the unknown and walks it like a pet.

It promises: don’t worry, the universe is looking after you. Everything happens for a reason. Your suffering is a lesson. Your losses are planned. Your destiny is aligned.

But the universe, as far as we can honestly tell, makes no such promises.

Reality is not obliged to be moral. It is not obliged to be comforting. It is not obliged to reward virtue. It is not obliged to make narrative sense.

Accepting this is not nihilism.

It is adulthood.

One of the most spiritual acts available to a human being is to refuse to lie about reality in order to feel safe.

This refusal is not harshness.

It is devotion.

It is saying: I love truth more than comfort. I love existence enough to let it be what it is, not what I wish it to be.

Here my spirituality lives.

It lives in the felt enormity of things.

In the fact that matter can wake up and become conscious.

In the fact that time produces love, and then takes it away.

In the fact that beauty exists at all — unrequired, unexplainable, extravagant.

In the fact that the night sky does not need human meaning and yet continues to move us.

In the fact that the world can be known in fragments and never wholly owned.

My spirituality lives in the discipline of attention: in looking closely without claiming too much; in being moved without becoming gullible; in allowing mystery to remain mysterious.

It also lives in ethics.

Because Woo is not merely mistaken; it is often immoral. Not always deliberately. But functionally.

To sell certainty without warrant is immoral.

To encourage belief without justification is immoral.

To tell the grieving that you know what you cannot know is immoral.

To tell the sick that their illness is a spiritual failure is immoral.

To tell the vulnerable that they must suspend discernment to be “open” is immoral.

Open-mindedness is not the elimination of standards. It is the continuous refinement of them.

A person who will believe anything is not open-minded.

They are undefended.

They are an unlocked house in a world where predators exist.

Predators do exist — not only cynical ones, but sincere ones intoxicated by their own stories. People who mistake sincerity for truth. People who cannot distinguish the intensity of a feeling from the accuracy of a claim.

This distinction — between feeling and claim — is the fulcrum.

You can feel the sacred without claiming supernatural knowledge.

You can experience transcendence without inventing metaphysics.

You can be spiritually moved without being epistemically irresponsible.

In fact, true spirituality requires epistemic responsibility.

What is more reverent: to stand in the unknown and say, “I do not know,” or to plaster the unknown with fantasies because silence makes us uneasy?

What is more sacred: to meet existence as it is, or to sell existence a costume?

We live in a time when many people are starving for depth. They are tired of being told that only what can be counted is real. They long for soul.

I understand this hunger. I share it.

But the answer is not spiritual junk food. Not comforting fiction. Not belief unmoored from reality.

The answer is to learn how to stand in wonder without lying.

To learn how to endure the sublime without grasping at certainty.

To learn that meaning is not always a message from above. Sometimes meaning is what we make through how we live, how we love, how we attend.

Sometimes the universe does not speak.

Sometimes it simply is — and our task is not to interpret it as a parent, but to meet it as a vast presence and respond with seriousness.

In the end, I do not push back against Woo because I am hostile to spirituality.

I push back because I am loyal to it.

Because spirituality, for me, is not a costume. Not a performance. Not a way to feel special. Not a set of claims.

It is the lived relationship between the human mind and the fact of existence.

It is the ability to be struck silent by reality.

It is the humility to admit the limits of knowledge.

It is the courage to refuse invented answers.

And it is the willingness to say — even when the heart aches for certainty:

We don’t know for sure.

Not as a shrug.

As a vow.

As an honouring.

As devotion deep enough to remain honest rather than be soothed.

Let the mystery remain a mystery.

That is not impoverishment.

That is reverence.

Also in Library

Naga Vow

2 min read

A lost city sleeps in the jungle, its thresholds carved with serpents — not ornament, but law. This vow-poem enters love as sacred hunger: desire as guardianship, devotion as possession, the body speaking without language. A liturgy of heat, roots, rain, and the terrible tenderness of being claimed.

The Meaning of Life Is a Vow

8 min read

Most lives do not collapse. They thin. They become functional, organised, reasonable—until the soul forgets what a life is for. Meaning is not granted. It is built: through illness, through love, through art, through grief—through the slow discipline of fidelity, and the choice of a centre that will not be betrayed.

The Line That Is Not a Line

9 min read

A boundary is drawn, and suddenly what was always present becomes “nothing.” This is one of the oldest spells: definition posing as neutrality, metaphor disguising jurisdiction, emptiness manufactured so extraction can begin. To resist is to attend—to name rightly, to refuse the comfort of false clarity, and to honour the world’s gradients.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.