Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

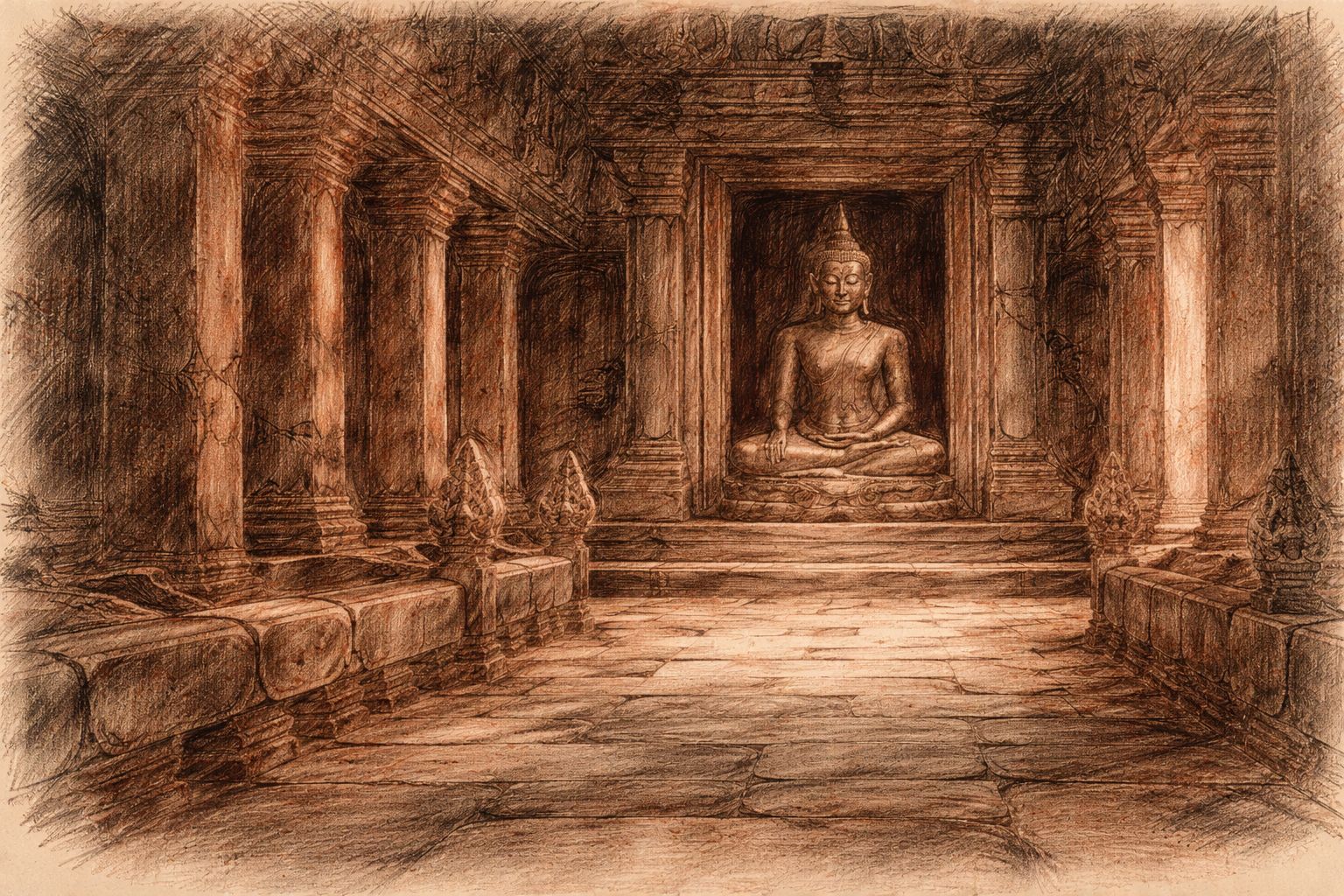

The Bodhisattva and the Discipline of Remaining

2 min read

In Angkor, the Bodhisattva is not announced. He does not arrive with doctrine or command. He is encountered in posture, in pause, in the way stone seems to hesitate before completion. The figure stands—or sits—at the threshold, neither withdrawn from the world nor fully absorbed by it. What defines him is not attainment, but restraint.

The word bodhisattva appears early in the tradition, but here it takes on weight through placement rather than explanation. It is a presence shaped to remain. Not a being in transit, but one who has chosen to stop where others would pass through. In this refusal of finality, the Bodhisattva becomes legible as an ethic rather than an ideal.

In Angkorian space, compassion is not sentimental. It is architectural. It takes the form of repeated galleries, long causeways, faces turned outward. The Bodhisattva looks not because he must intervene, but because he has not turned away. His gaze does not resolve suffering; it acknowledges it, without haste.

This stance carries cost. To remain is to accept delay, weight, repetition. The Bodhisattva does not escape the world’s friction; he absorbs it, holds it long enough for others to pass. What he renounces is not enlightenment itself, but the privilege of leaving first.

Stone records this choice obliquely. Figures are carved with ornaments and crowns, yet their eyes are lowered. The body is adorned, but the gesture is quiet. Power is present, yet it is bent inward, disciplined by attention. Nothing is grasped. Nothing is released prematurely.

In the Angkorian imagination, the Bodhisattva becomes a measure for rule, for care, for making. To govern is not to ascend, but to remain exposed to consequence. To build is not to dominate space, but to make room for return. To act is to do so without exhausting the world’s patience.

The Bodhisattva does not promise rescue. He promises accompaniment. He stays close enough that suffering is not alone, yet distant enough that it must still be borne. This balance—neither intervention nor abandonment—is what gives the figure his gravity.

To encounter the Bodhisattva here is to sense a refusal that stabilises the world. A refusal to conclude. A refusal to abandon the unfinished. In that refusal, continuity becomes possible.

Also in Library

The Devata at First Light

8 min read

At first light in Banteay Kdei, a devata draws the eye into stillness. Through sanguine chalk, black shadow, and repeated returns to the page, sketch and prose slowly deepen into a single act of devotion—until the words, too, learn how to remain.

The Spark and the Weight of Being Human

9 min read

At some point in our past, a human asked the first question—and self-awareness was born. Yet the same consciousness that gave us power also confronts us with our limits. This essay explores the paradox of being human: the spark of understanding and the weight of knowing.

The Pact of the Uncounted Grain

10 min read

A village does not starve only when rice runs out. It begins to thin when everything is counted, explained, and held too tightly. The Pact of the Uncounted Grain remembers an older law: that once each season, abundance must pass through human hands without measure, or the world begins, quietly, to lose its meaning.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap — reflections, field notes from the temples of Angkor, and glimpses into the writing and creative life behind the work.

When you subscribe, you will receive a complimentary digital copy of

Three Ways of Standing at Angkor — A Pilgrim’s Triptych, a short contemplative book on presence, attention, and the art of standing before sacred places.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet words, delivered gently.

Subscribe and step into the unfolding journey.