Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

The Measure of Silence: A Pilgrim’s Reflection on Kingship at Angkor

10 min read

The wind moves through broken corridors, carrying the faint scent of rain and time. Beneath the weight of lichen and silence, the old kings are listening.

The first light over Angkor is never the same twice.

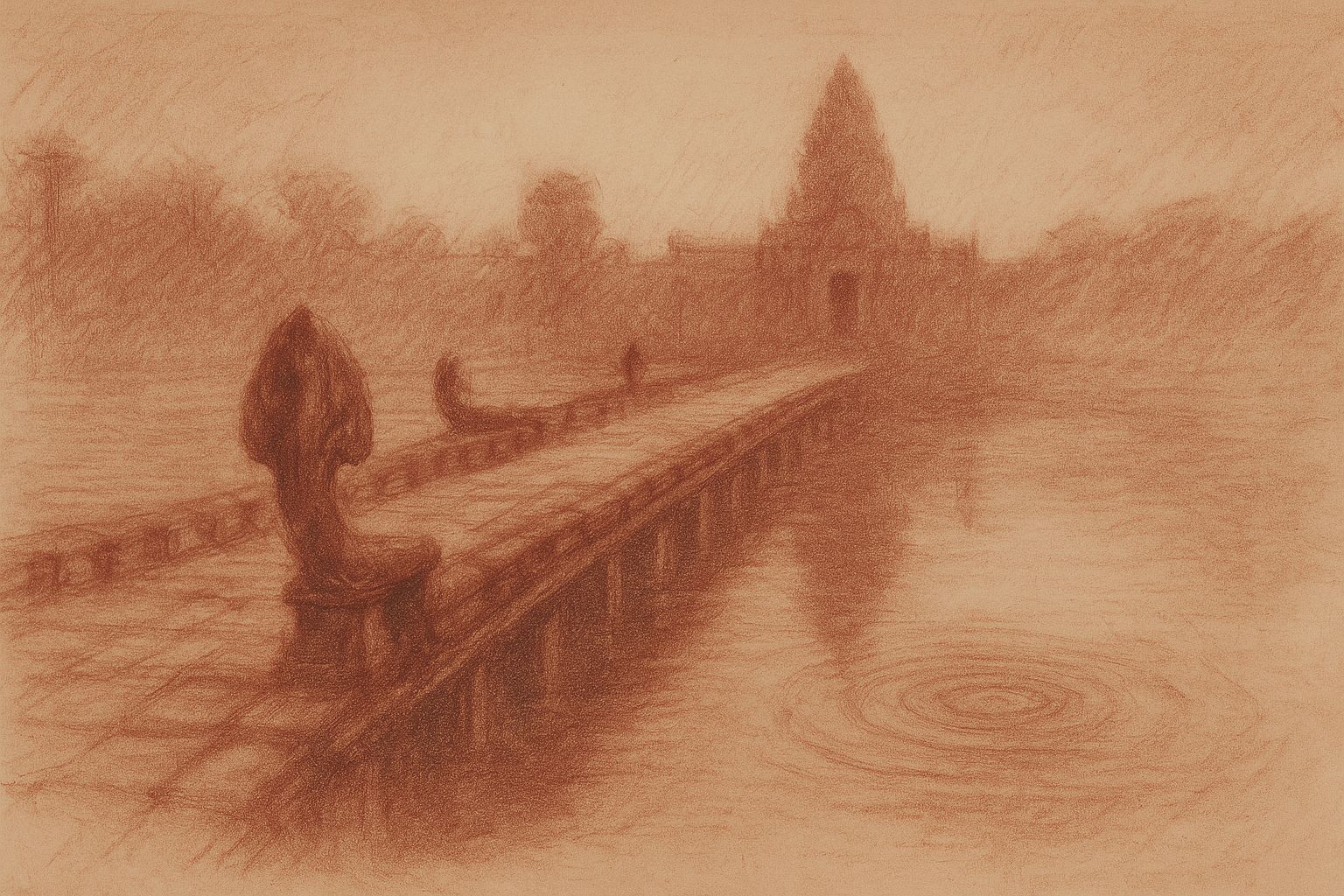

It slips through the galleries of stone as if testing their patience, brushing the faces of devas and lions, touching the faint outlines of epics long surrendered to moss. I stand where the moat mirrors the sky—a thin divide between worlds—and watch the reflection of towers that were meant to hold the sun itself.

The city lies quiet now, emptied of its kings. The roads that once bore elephants and the chants of consecration lead only to stillness. Yet in the pattern of each carved vine, in the slow pulse of shadow across bas-relief, something endures: a murmur of devotion, a geometry of faith.

To walk these corridors is to move within memory rather than ruin. The walls remember when power was a ritual, when kings built mountains to mirror heaven, and when the earth was believed to breathe through the hands of those who shaped its stone. They remember the voices of Jayavarman and Suryavarman, Indravarman and Yasovarman—names that sound like thunder softening into prayer.

What remains of their world is not the noise of conquest but the discipline of alignment. Each stone was laid with intention, each gallery designed to orient the spirit toward the centre, where silence becomes divine proportion. Kingship here was not merely rule; it was cosmology made visible. The sovereign was the axis between earth and sky, the embodiment of balance and fertility, of Siva’s stillness and Vishnu’s sustaining grace.

Yet standing among these stones, I feel the weight of that order as absence. The perfection they sought—encoded in measure and myth—has fallen into dust, and the symmetry of their power now serves only the symmetry of decay. The same hands that lifted devotion skyward could not hold back time.

Beyond the moat, the jungle gathers at the edges. Banyan roots pry apart sanctuaries once guarded by fire. Parrots cry where courtiers once spoke Sanskrit verse. Every ruin is a sermon on impermanence, every fallen lintel a verse in the unfinished hymn of kingship.

I trace the incised lines of an inscription—half-erased words praising Indravarman, protector of rain and order. The letters rise like the ribs of a buried animal. Each mark was once a vow: to sustain the gods, to feed the temple’s slaves, to maintain the reservoirs that kept the kingdom alive. Their precision speaks of certainty, but I sense behind it the human need to bind chaos through ritual. The Angkorean monarchs did not merely command; they consecrated. Their irrigation works were acts of worship, their wars reflections of celestial conflict.

In their imagination, the king was both priest and engineer, the one who coaxed abundance from earth by imitating the structure of heaven. When Indravarman ordered the digging of the Indratataka in the ninth century, he was not building a lake but invoking a cosmogram—a mirror of the sacred mountain encircled by waters. To fill the reservoir was to complete a gesture begun in myth: the recreation of creation itself.

Now the basin lies dry, its embankments scattered with grass and cattle. Children play where royal barges once floated like processional stars. The silence is immense. Yet the idea persists—that devotion can be built, that the alignment of body and cosmos can be achieved through architecture. Angkor is the record of this faith, written not in scripture but in symmetry.

Walking deeper into the complex, I pass through doorways worn by centuries of pilgrims. Each threshold is a breath: heat to cool, light to shadow. The temples repeat themselves in infinite variation—brick giving way to sandstone, relief to void—as if the builders were rehearsing eternity. Here, in the silence, the city becomes a teacher. It reveals that kingship, for all its grandeur, was always a fragile covenant between ambition and belief.

They called their land Kambuja-desa, the world of men blessed by the gods. Its rulers carried titles drawn from Sanskrit, yet their power grew from Cambodian soil, from the sweat of those who dug the barays and carried the stones. Their cosmology was imported, but their devotion was local—earth-born, humid, luminous.

The Sdok Kak Thom inscription speaks of Jayavarman II ascending the Kulen Hills in 802 to perform the rites that would make him chakravartin, the universal monarch. From that act, legend tells us, Angkor was born: not merely a kingdom but a vision of the world ordered through divine kingship. The ceremony bound the monarch to Siva, establishing the devarāja—the god-king—whose body mirrored the cosmos and whose city mirrored heaven.

But what does such a claim mean when spoken into silence? The Kulen plateau still rises above the plain, its streams feeding the Tonlé Sap, its stones carved with the linga of ancient offerings. Yet the forest has reclaimed its shrines, and the chants of consecration have given way to the wind through bamboo. The universal monarch returned to dust, his universal order to myth.

It is tempting to see this as hubris punished, yet I feel instead the poignancy of devotion misread by time. Jayavarman’s act was less about domination than about coherence. To be king was to maintain the delicate circulation between heaven’s law and earth’s yield—to ensure that rain fell, that ancestors were appeased, that the world’s axis did not falter.

When the rains came, the reservoirs filled and the paddies shone like mirrors of the sky. When they failed, the same people who had sung hymns to the king’s divinity would whisper doubts in the dark. Kingship was thus a weather of faith, measured by harvest and flood. It demanded ceaseless proof, renewed through offerings, architecture, and war.

Inscriptions speak of Jayavarman moving across the land—Ba Phnom, Sambor, Hariharalaya—binding scattered regions into a single imagination. His progress was both political and sacred, each conquest an act of ritual consolidation. The kings who followed him inherited not merely territory but a template for legitimacy: to build, to consecrate, to leave stone where others left wind.

At Roluos, Indravarman raised the Preah Ko and Bakong, aligning the human and divine through brick, stucco, and water. Each monument proclaimed order in a landscape of flux. The temples were not symbols of power so much as instruments of balance: artificial mountains surrounded by moats, mirroring the mythic Meru ringed by oceans. Within their chambers, statues of ancestors were enshrined as gods, fusing lineage and divinity. The city became a genealogy of stone.

I pause at the edge of Bakong’s stepped pyramid. Its terraces climb in measured humility toward a summit that once held the king’s ashes. The air smells of dust and honey. Nearby, monks sweep leaves into circles that mimic the temple’s form—concentric, deliberate, temporary. Everything returns to pattern.

From this height one can imagine the order that once pulsed through the plain: the barays gleaming with captured sky, the causeways alive with procession, the rice fields stretching toward a horizon of belief. Yet even in their prime, these structures carried the seeds of stillness. To enshrine eternity is to invite it prematurely. The perfection of Angkor was always a rehearsal for ruin.

When Yasovarman I moved the capital to Angkor in the late ninth century, he sought not novelty but refinement—a geometry capable of housing divine proportion. He built his city around a hill, Phnom Bakheng, the axis of a newly consecrated world. From its terraces, the sun rose and set in measured ritual, aligning celestial order with royal command.

To climb Phnom Bakheng at dusk even now is to feel that alignment. The jungle murmurs below, the air turns to gold, and the towers of Angkor Wat glow in the distance like embers of a forgotten theology. Tourists whisper, cameras click, yet for a moment the ancient equation reveals itself again: elevation as revelation, height as holiness.

Yasovarman’s reign marked the flowering of what might be called the Angkorean idea—the belief that architecture could embody salvation, that a city could be a cosmogram. Around his central mountain he built reservoirs, monasteries, hermitages, and rest houses for pilgrims. The network extended like veins through the kingdom, carrying not just water but blessing.

His successors expanded the pattern. Some reigned briefly, their names flickering through inscriptions like torches in the rain; others, like Rajendravarman and Jayavarman V, gave the city new complexity and grace. Their temples—Pre Rup, East Mebon, Banteay Srei—combined intimacy and intricacy, stone turned to lace. Here devotion became craftsmanship, and craftsmanship devotion.

Banteay Srei, carved from pink sandstone, remains the most human of the Angkorean sanctuaries. Its scale invites touch. The devatas smile not with majesty but with memory, as if recalling the hands that shaped them. Dedicated not by a king but by his guru, it stands as an act of personal piety within an empire of divine claims. In its reliefs, the myths of Vishnu and Siva unfold not as cosmic battles but as parables of attention—the god’s infinite in the carver’s finite line.

By the time Suryavarman I seized power in the early eleventh century, kingship had become both art and burden. The kingdom stretched across rice plains and mountains, reaching toward what are now Thailand and Laos. His rule was administrative, almost bureaucratic, yet charged with metaphysical ambition. The inscriptions describe him binding the land through oaths of loyalty, his officials swearing fealty under the threat of rebirth in the thirty-second hell.

Such oaths may sound severe, but they were acts of unification—a moral architecture mirroring the hydraulic one. To swear was to be woven into the kingdom’s pulse, to become part of the same network that channelled water and faith. Loyalty was irrigation of the spirit.

Suryavarman’s vision extended westward to the Buddhist city of Lopburi and eastward to the Cham frontier. His armies marched, but his monuments spoke more lastingly: temples multiplying, reservoirs widening, the geometry of power refined once more. The city became a mandala of governance, its centres shifting as kings rose and fell, yet always anchored to the principle that order was sacred imitation.

What strikes me, reading the stones, is how the vocabulary of sanctity replaced that of policy. Where other civilizations recorded decrees, Angkor recorded consecrations. The line between temple and state blurred until each sustained the other. Priests were administrators; administrators were patrons of the gods. The bureaucracy became a liturgy, the economy a ritual of reciprocity between seen and unseen worlds.

And yet the cracks were already beginning to show. To maintain the sacred machine required endless labour—slaves, cultivators, artisans, and scribes whose lives were consumed by devotion’s logistics. Inscriptions name them with chilling precision: men and women, their children listed by age and mobility, their tasks enumerated. Each offering of gold or grain required human maintenance. Behind the grandeur of Angkor lay an invisible multitude sustaining its illusion of permanence.

I think of them when I watch the light fade across the Bayon’s faces—those serene visages that seem to see without judgment. They might be kings or gods or the composite spirit of both. Perhaps they are also the echo of the countless unknown who lifted the stones. Their silence is the truest monument here.

By the time Suryavarman II ascended the throne in the twelfth century, the empire had reached a scale that no longer required justification—only continuation. Yet Suryavarman understood kingship as a cosmic trust, not inheritance. His reign brought the construction of Angkor Wat, a temple so vast it might have seemed the world itself trying to remember its own design.

The temple opens westward, into the setting sun—the direction of death. Pilgrims still walk its causeway at dawn, not realising they move against the grain of intention. For Angkor Wat is both sanctuary and tomb, its galleries leading inward and backward through myth, through time itself. The bas-reliefs begin with the Churning of the Sea of Milk, where gods and demons strain at the serpent Vasuki to bring forth amrita, the nectar of immortality. But here, immortality was a question, not an answer.

Suryavarman dedicated his temple to Vishnu, the preserver, yet he built it as his own sarcophagus. The alignment of its stones mirrors the cosmic ages—the yugas of Indian thought—measured not in years but in breaths of the universe. To walk from the western gate to the central tower is to traverse creation backward, from the Kali Yuga of darkness toward the Krita Yuga of light. Each step a turning of time’s wheel.

At the solstice, the sun rises directly above the central tower. The geometry is immaculate, the metaphor inexhaustible: kingship as astronomy, faith as architecture, death as alignment. Standing before it now, centuries later, I feel the same pull that must have drawn Suryavarman to imagine the impossible—a temple where eternity could be rendered measurable, where the divine could be housed within human proportion.

But perfection has a cost. Even as Angkor Wat rose from the plain, the system that sustained it began to falter. The reservoirs silted, the canals slowed, the labour force strained. The equilibrium between vision and sustenance—between heaven’s pattern and earth’s capacity—tilted. And when the balance failed, the city that had mirrored the cosmos began to collapse under the weight of its own symmetry.

By the close of the twelfth century, rebellion flared, and the kingship fractured. Yet from that turmoil emerged one final brilliance: Jayavarman VII, the last great builder. A devout Buddhist, he reimagined kingship not as divine isolation but as compassion enacted through stone. His Bayon, with its multitude of serene faces, turned the architecture of dominion into the architecture of empathy. The king became Bodhisattva; the city, a mandala of mercy.

Hospitals, rest houses, roads—Jayavarman’s works were the arteries of a new kind of order. Yet even compassion, monumentalised, becomes tyranny of form. When his reign ended, the great wheel turned again toward silence. The jungle advanced, the reservoirs failed, and the once-bright geometry dissolved into shadow.

I walk now along the moat of Angkor Wat at twilight. The water holds the reflection of towers and clouds; bats flicker like ash over the surface. The air smells of rain. Somewhere, a monk’s bell rings—a thin sound carried far across the dark.

It is here, in this hour between light and loss, that the meaning of Angkor reveals itself. The kings built to preserve the rhythm between heaven and earth, but what they achieved was a vast equation of impermanence. Every temple, every canal, every inscription was a negotiation with time—a promise that beauty might momentarily outlast decay.

Now the promise remains fulfilled only in fragments. The faces at Bayon still smile, though their mouths are broken. The reservoirs still gather rain, though their embankments crumble. The people who walk these paths do so without knowing the names of the kings beneath their feet. And yet, in the hush of evening, the air itself seems consecrated—as if the devotion of centuries has seeped into the soil.

Angkor endures because it failed beautifully. Its ruins are not reminders of loss but revelations of measure: that even the greatest harmonies fade, and that in their fading lies the truest symmetry of all.

When I leave the temple, the last light catches the tips of the lotus towers, turning them to ember. The sky darkens. Fireflies rise from the grass, small souls rehearsing resurrection. Somewhere beyond the forest, the ancient reservoirs wait for rain.

The kings are silent now. But their silence is not absence—it is continuation. In it, the pilgrim hears the echo of what once was order, and what remains eternal: the desire to build toward the light, even knowing it will pass.

Also in Library

Before the Shutter Falls

3 min read

Before the shutter falls, fear sharpens and doubt measures the cost of waiting. In the quiet hours before dawn, the act of not-yet-beginning becomes a discipline of attention. This essay reflects on patience, restraint, and the quiet mercy that arrives when outcome loosens its hold.

Those Who Keep the Way Open — On the Quiet Guardians of Angkor’s Thresholds

3 min read

Quiet gestures shape the way into Angkor — a swept stone, a refilled bowl, a hand steadying a guardian lion. This essay reflects on the unseen custodians whose daily care keeps the thresholds open, revealing how sacredness endures not through stone alone, but through those who tend its meaning.

Multiplicity and Mercy — The Face Towers of Jayavarman VII

5 min read

A new vision of kingship rises at the Bayon: serene faces turned to every horizon, shaping a world where authority is expressed as care. Moving through the terraces, one enters a field of steady, compassionate presence — a landscape where stone, light, and time teach through quiet attention.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.