Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

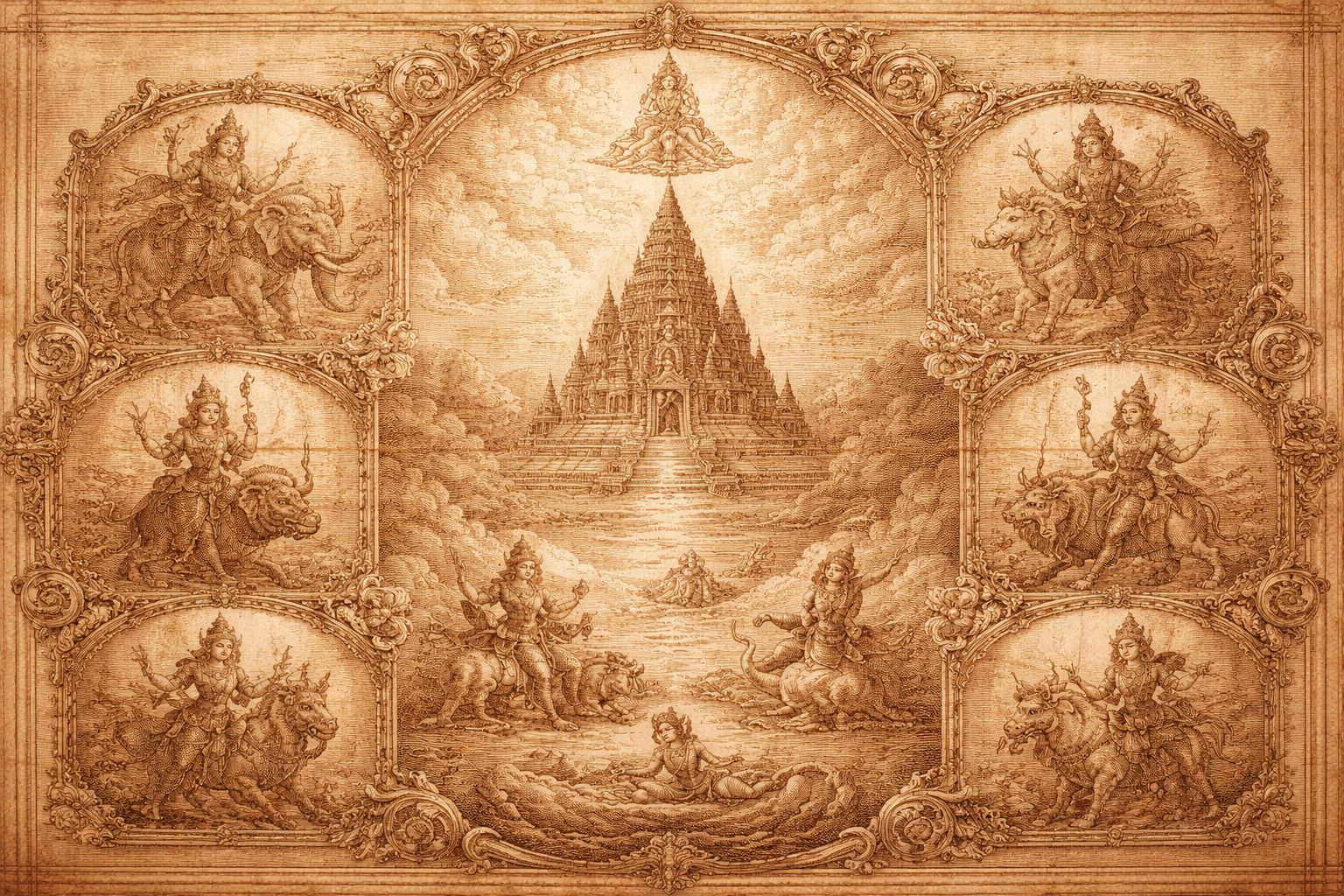

The Dikpalas — Holding the World in Place

A temple does not begin at its doorway. It begins earlier—at the moment the body senses direction. East is felt before it is named. West gathers weight in the afternoon light. North cools the breath; south presses warmth into the stone. Long before doctrine or inscription, the world announces itself through orientation. The Dikpalas arise from this awareness. They are not inventions of myth so much as recognitions of a condition already present: that space itself must be held.

The Dikpalas—also called Lokapalas—are the Guardians of the Directions. They rule not over stories but over territories. Each god governs a sector of space: the four cardinal points, the four intercardinal intervals, and, in expanded cosmologies, the zenith above and the nadir below. Together they form a complete enclosure, a divine perimeter within which order can exist. Without them, space would be open, unbounded, and therefore unsafe.

In the earliest Vedic imagination, the world is not neutral. Directions carry ethical charge. To move eastward is not the same as turning south. Each direction has consequence. Indra presides over the east, where kingship, sky, and authority rise with the sun. Agni governs the south-east, the threshold of fire and transformation. Yama stands in the south, judge and regulator of death, ensuring that endings remain measured. Nirriti occupies the south-west, the most precarious quarter, where dissolution, sorrow, and hidden realms collect. Varuna rules the west, keeper of waters and vows, the god of moral restraint as much as oceans. Vayu moves through the north-west, animating the world with wind and breath. Kubera holds the north, storing wealth, fertility, and accumulation. Ishana presides over the north-east, where knowledge and sovereignty converge.

Above them, Brahma crowns the zenith, and beneath them Vishnu anchors the nadir. The cosmos is sealed from every side.

In the Khmer world, these deities are not abstract. They are installed. Their images appear on lintels, pillars, pediments, and thresholds—not as decoration, but as structural necessity. A temple without directional guardians would be cosmologically unfinished. By carving the Dikpalas into stone, Khmer architects fixed the building into the grid of the universe. The temple became not a shelter for worship, but a working model of the world.

This is why the temple-mountain matters. Its form does not merely symbolise Mount Meru; it activates it. The central tower establishes the vertical axis. The terraces articulate hierarchies of being. The moat draws the primordial ocean close and still. But it is the Dikpalas who hold this structure in equilibrium. They prevent drift. They ensure that power does not leak from one direction into another, that water does not overwhelm fire, that death does not wander north, that wealth does not accumulate without limit.

In Khmer adaptation, these guardians change subtly. Mounts are altered. Vayu rides a lion instead of an antelope. Agni appears on a rhinoceros, a distinctly local intervention. Varuna may sit upon a naga or a hamsa rather than a makara. These are not errors or deviations. They are acts of translation. The cosmology remains intact, but it is spoken in a Khmer accent.

Over time, the balance shifts. Vishnu comes to dominate the west. Shiva advances into the north-east, sometimes even the east itself. The old Vedic order is not discarded, but re-weighted. In the temples associated with Jayavarman VII, Shiva’s presence is often felt along the northern axis—a quiet but decisive reorientation of the cosmic map. Direction is never static. It responds to theology, kingship, and historical moment.

Yet the underlying principle holds. A temple must be oriented, guarded, and sealed.

The Dikpalas are therefore not warriors in the ordinary sense. They do not defend against invasion. They defend against confusion. They ensure that thresholds remain thresholds, that transitions occur in the correct order. Their authority is ethical rather than martial. Varuna governs vows. Yama judges fairness. Kubera regulates excess. Even Nirriti, feared and avoided, has her place—holding the realms that must not bleed into the living world.

Seen this way, the Dikpalas are less like soldiers than surveyors. They mark limits. They say: this far, and no further. In a civilisation built on water management, seasonal rhythm, and architectural precision, this role is not symbolic—it is existential.

To walk through an Angkor temple attentively is to feel these forces at work. One turns a corner and senses a change in gravity. A causeway aligns the body east-west with unmistakable insistence. A doorway compresses space, and the dvārapālas stand ready—not to threaten, but to confirm that one has arrived at a point of transition. Beyond them, devatas inhabit the walls, no longer guarding but sanctifying, turning structure into dwelling.

The Dikpalas operate at a deeper register. They do not welcome. They do not bless. They hold.

In an age inclined toward boundlessness, their lesson is severe and necessary. Order is not imposed through dominance, but through placement. Power is not amplified by expansion, but by restraint. To know where one stands—north, south, east, or west—is to know how to act.

The temples of Angkor endure not because they are monumental, but because they are correctly aligned. Stone survives when it knows its direction.

Also in Library

The Devata at First Light

8 min read

At first light in Banteay Kdei, a devata draws the eye into stillness. Through sanguine chalk, black shadow, and repeated returns to the page, sketch and prose slowly deepen into a single act of devotion—until the words, too, learn how to remain.

The Spark and the Weight of Being Human

9 min read

At some point in our past, a human asked the first question—and self-awareness was born. Yet the same consciousness that gave us power also confronts us with our limits. This essay explores the paradox of being human: the spark of understanding and the weight of knowing.

The Pact of the Uncounted Grain

10 min read

A village does not starve only when rice runs out. It begins to thin when everything is counted, explained, and held too tightly. The Pact of the Uncounted Grain remembers an older law: that once each season, abundance must pass through human hands without measure, or the world begins, quietly, to lose its meaning.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap — reflections, field notes from the temples of Angkor, and glimpses into the writing and creative life behind the work.

When you subscribe, you will receive a complimentary digital copy of

Three Ways of Standing at Angkor — A Pilgrim’s Triptych, a short contemplative book on presence, attention, and the art of standing before sacred places.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet words, delivered gently.

Subscribe and step into the unfolding journey.