Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

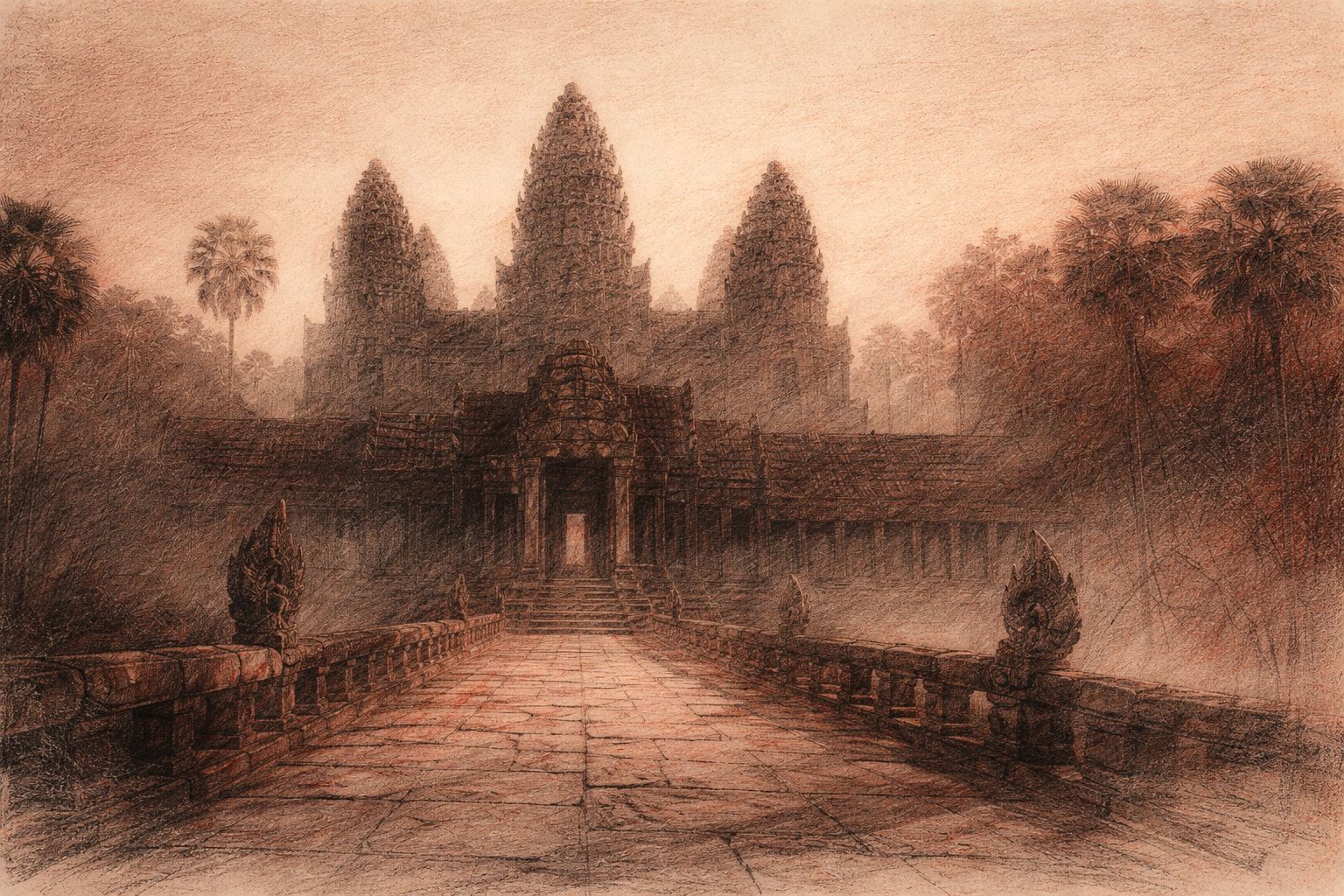

The End of Sanskrit at Angkor

2 min read

There is a point at Angkor where language ceases to sound like proclamation and begins to register as residue. Not silence exactly, but something quieter than command. The stone still stands, the galleries still breathe shadow and rain, yet the voice that once addressed gods directly withdraws, leaving the syllables unfinished in the ear.

For centuries, Sanskrit had spoken here with assurance. It named kings, tethered lineages to the heavens, bound the work of masons and priests into a single grammatical order. Its cadence was not conversational; it did not persuade or invite. It declared. To carve in Sanskrit was to assume continuity—of rule, of cosmology, of the gods’ attention. Each inscription was a gesture of permanence, a wager that stone and metre could outlast time.

But permanence is never neutral. It demands upkeep: ritual precision, learned custody, an unbroken chain of listening. By the early fourteenth century, that chain had thinned. The final Sanskrit inscription, dated 1327, does not announce an ending. It does not mourn itself. It simply appears—polished, exact, composed as if nothing had changed—already an anachronism in its own moment. A voice still capable of eloquence, speaking into a world that had begun to listen differently.

Around it, the spiritual climate had shifted. The slow diffusion of Theravada Buddhism altered not only doctrine but scale. Instruction moved from court to cloister, from genealogy to conduct, from cosmic architecture to the discipline of the body and the mind. Pali entered the region not as a rival language but as a more permeable one. It did not require elevation. It could be carried, memorised, repeated aloud. Its authority rested not in ornament but in use.

With this shift came a reorientation of material devotion. The great stone programmes ceased—not through collapse or decree, but through irrelevance. The temple-mountain no longer served the primary work of awakening. Wooden vihara rose instead, vulnerable to rot and renewal, aligned with a teaching that did not insist on endurance. Memory moved off stone and onto palm leaf, breath, gesture. What could not be preserved was no longer automatically worth preserving.

Sanskrit, in this context, did not fail. It completed its work. Its withdrawal marks not a loss of intellect, but a redistribution of attention. The language of cosmic address gave way to one concerned with suffering, impermanence, and release. The gods receded from architectural centre stage, and the human path—walked, repeated, corrected—took precedence over monumental proof.

Today, the absence is palpable only if one listens for it. The walls do not complain. They accept moss, water, and the passing of feet. Yet embedded in their silence is the memory of a voice that once assumed it would always be heard. The end of Sanskrit at Angkor is not a rupture in history so much as a soft relinquishment: the moment when the civilisation stopped asking stone to speak forever, and allowed meaning to travel by more fragile means.

Also in Library

The Devata at First Light

8 min read

At first light in Banteay Kdei, a devata draws the eye into stillness. Through sanguine chalk, black shadow, and repeated returns to the page, sketch and prose slowly deepen into a single act of devotion—until the words, too, learn how to remain.

The Spark and the Weight of Being Human

9 min read

At some point in our past, a human asked the first question—and self-awareness was born. Yet the same consciousness that gave us power also confronts us with our limits. This essay explores the paradox of being human: the spark of understanding and the weight of knowing.

The Pact of the Uncounted Grain

10 min read

A village does not starve only when rice runs out. It begins to thin when everything is counted, explained, and held too tightly. The Pact of the Uncounted Grain remembers an older law: that once each season, abundance must pass through human hands without measure, or the world begins, quietly, to lose its meaning.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap — reflections, field notes from the temples of Angkor, and glimpses into the writing and creative life behind the work.

When you subscribe, you will receive a complimentary digital copy of

Three Ways of Standing at Angkor — A Pilgrim’s Triptych, a short contemplative book on presence, attention, and the art of standing before sacred places.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet words, delivered gently.

Subscribe and step into the unfolding journey.