Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

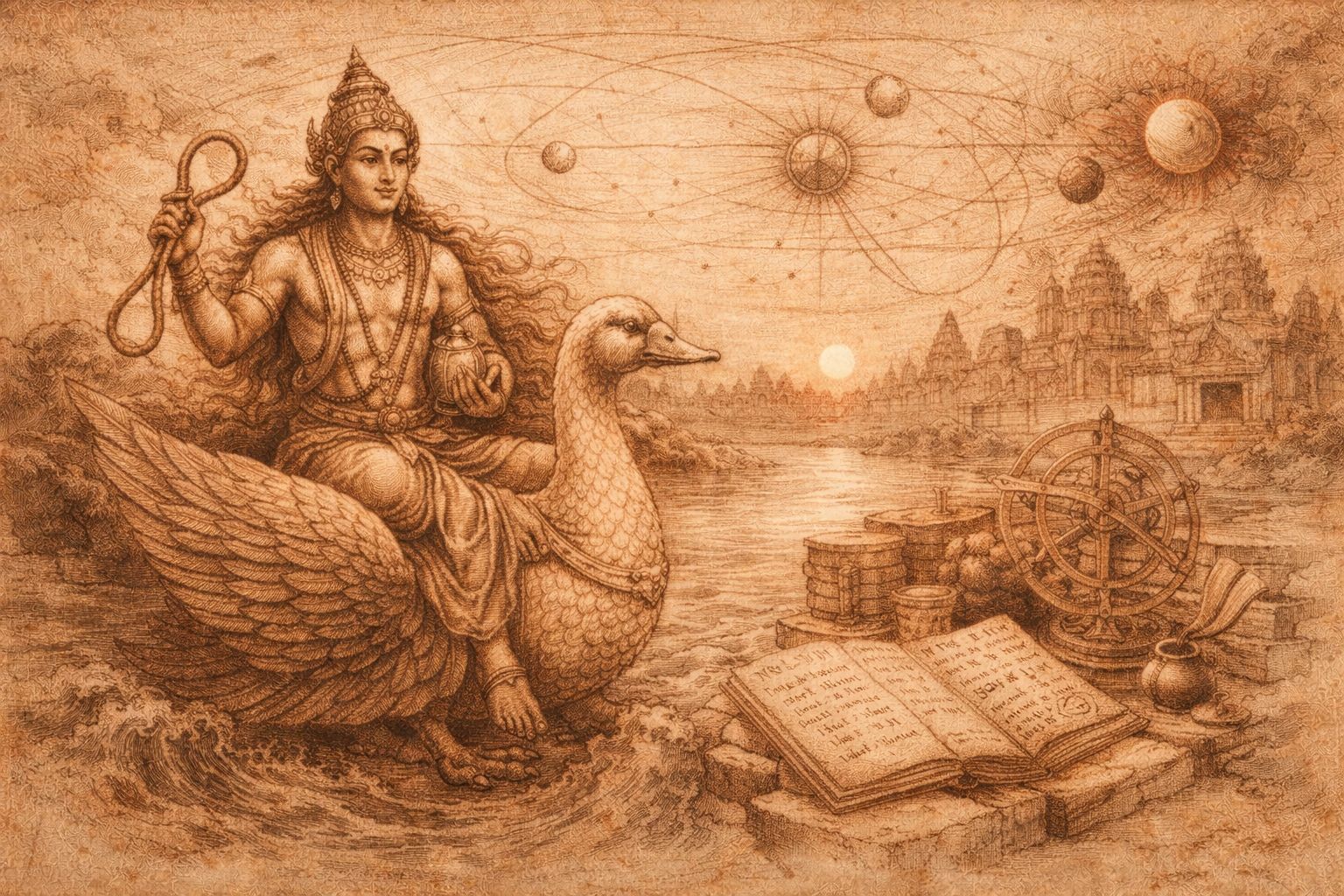

Varuna Within Planetary Order

2 min read

Varuna is easiest to misunderstand when removed from time.

Read only through later mythology, he appears to narrow: a water god, a moral enforcer, a guardian displaced by more charismatic deities. Read within the Navagraha, his function sharpens. He becomes legible not as an isolated figure, but as part of a working system—one concerned with flow, measurement, and passage.

In Khmer cosmology, Varuna is aligned with Mercury and with Wednesday: the planet and day associated with movement between states. Mercury governs rivers, bridges, trade, writing, calculation, and communication. It is the planet of connection rather than dominance, of transmission rather than command. This association explains much that otherwise appears secondary or contradictory in Varuna’s character.

Water, in this context, is not elemental abundance. It is circulation. It moves through channels. It links reservoirs. It must be measured, released, restrained. Varuna’s authority is exercised not through force, but through calibration. His noose binds not to punish, but to prevent drift—ethical, temporal, or material.

This planetary placement also clarifies Varuna’s frequent appearance in architectural contexts associated with record, calculation, and timing. Navagraha slabs positioned in temple libraries are not decorative. They mark the point where inscription meets sky—where consecration dates are fixed, where cosmic order is consulted before stone is raised. Varuna’s presence here signals that water, time, and law are inseparable.

Mercury does not rule beginnings or endings. It governs transitions. Varuna’s guardianship of the West, inherited later by Vishnu, belongs to this same logic. The West is the quarter of return, accounting, and closure. What has flowed outward must be gathered. What has been initiated must be reconciled.

Seen this way, Varuna is not diminished by his placement within the Navagraha. He is specified. His role is to ensure that time does not fracture under its own movement—that passage remains intelligible, that flow remains accountable. He stands wherever the world must be timed rather than celebrated.

This is why Varuna persists across the Journal: in water systems, in boundary-making, in inscriptions that name exact moments. He is present wherever time is handled carefully—where the cosmos is not invoked symbolically, but consulted operationally.

To recognise Varuna within planetary order is to understand that Angkor did not treat time as abstraction. It treated it as infrastructure.

And Varuna, quietly, was one of its engineers.

Also in Library

The Devata at First Light

8 min read

At first light in Banteay Kdei, a devata draws the eye into stillness. Through sanguine chalk, black shadow, and repeated returns to the page, sketch and prose slowly deepen into a single act of devotion—until the words, too, learn how to remain.

The Spark and the Weight of Being Human

9 min read

At some point in our past, a human asked the first question—and self-awareness was born. Yet the same consciousness that gave us power also confronts us with our limits. This essay explores the paradox of being human: the spark of understanding and the weight of knowing.

The Pact of the Uncounted Grain

10 min read

A village does not starve only when rice runs out. It begins to thin when everything is counted, explained, and held too tightly. The Pact of the Uncounted Grain remembers an older law: that once each season, abundance must pass through human hands without measure, or the world begins, quietly, to lose its meaning.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap — reflections, field notes from the temples of Angkor, and glimpses into the writing and creative life behind the work.

When you subscribe, you will receive a complimentary digital copy of

Three Ways of Standing at Angkor — A Pilgrim’s Triptych, a short contemplative book on presence, attention, and the art of standing before sacred places.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet words, delivered gently.

Subscribe and step into the unfolding journey.