Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

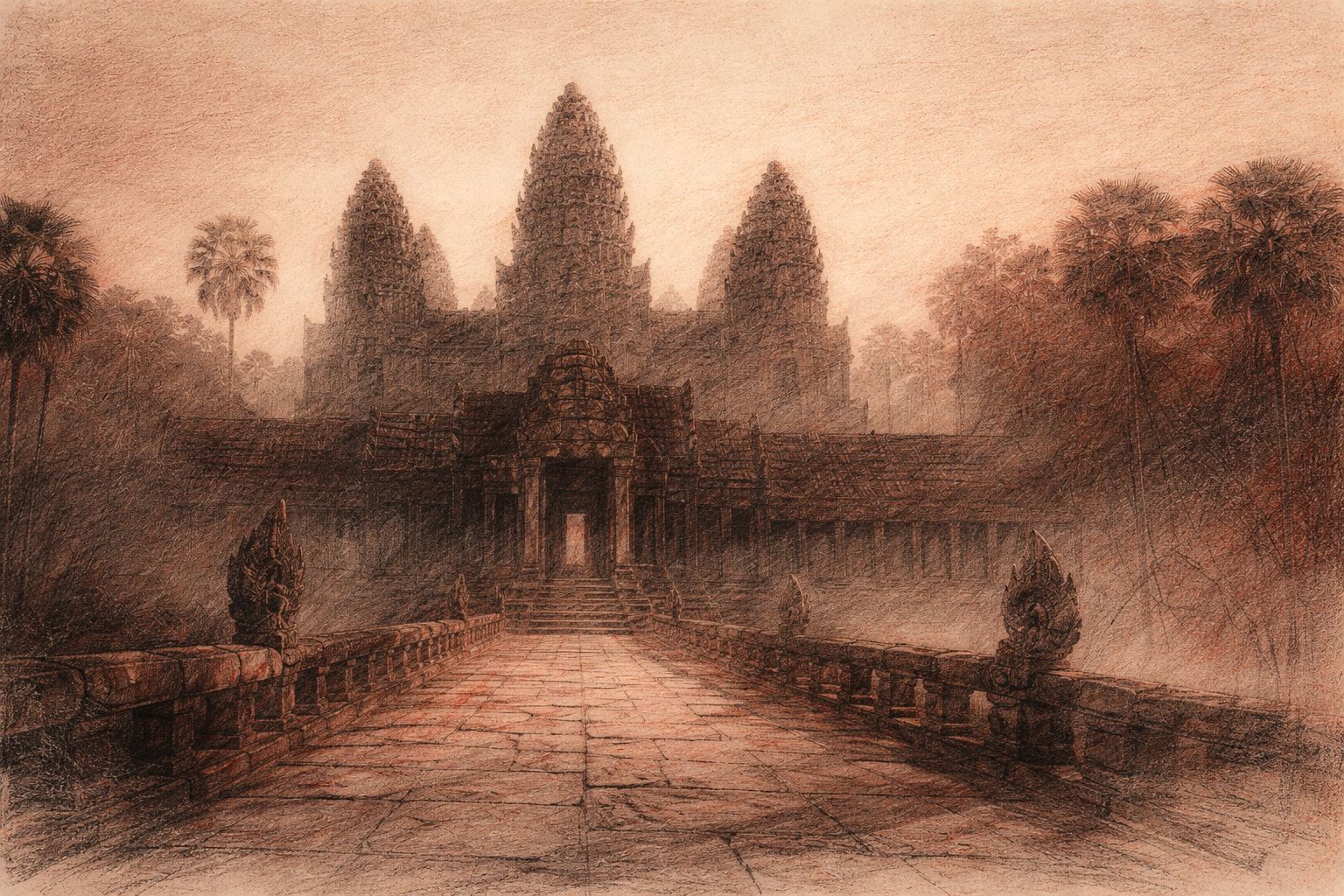

Varuna and Vishnu: The Western Guardians

The West is not where Angkor ends.

It is where things are completed.

In the earliest Vedic imagination, the West belonged to Varuna. Not as a place of decline, but as a domain of oversight—the quarter where the world must be accounted for before it disappears from view. Varuna ruled the wide sky before it darkened, the waters before they deepened, the moral law before it required enforcement. He did not govern beginnings. He governed consequences.

Varuna’s authority was never loud. He did not strike like Indra or blaze like Surya. He watched. The sun itself was said to be his eye. What passed beneath it could not escape record. To move westward was to move toward truth stripped of ornament, toward a horizon where intention and outcome meet.

Over time, this responsibility shifts. Vishnu assumes the western quarter—not by overthrow, but by inheritance. Preservation replaces judgement; continuity replaces restraint. Where Varuna bound falsehood with the noose, Vishnu stabilised the world by remaining within it. The West does not lose its gravity. It changes its task.

This transition mirrors a deeper cosmological rebalancing. Varuna belongs to an older order, where morality is enforced through cosmic law—ṛta—and deviation is dangerous. Vishnu belongs to a later vision, where the world is already fragile and must be held together through care, return, and measured intervention. The guardian remains; the method evolves.

Angkor absorbs this transformation without rupture.

In Khmer temples, Varuna appears first as guardian of waters and sky, riding the hamsa—creature of passage and discernment—then later as lord of rivers and oceans, seated upon the makara, embodiment of unseen depth. He becomes increasingly liminal: less sovereign, more custodial. His authority condenses rather than disappears.

Vishnu, meanwhile, rises not as conqueror of the West but as its fulfiller. His association with sunset, completion, and preservation finds its most exact architectural expression at Angkor Wat. The great temple does not face east into promise. It faces west into resolution. It is not oriented toward becoming, but toward being held in balance.

This is why Angkor Wat can function simultaneously as state temple, cosmic diagram, and funerary monument. The West, under Vishnu, is no longer a place of judgement alone. It becomes the place where the world is gathered, sustained, and allowed to endure beyond the life of its king.

Varuna does not vanish in this arrangement. He recedes into structure. Into water management, boundary-making, and the ethics of restraint. Vishnu does not replace him so much as stand where he once stood, carrying forward the same weight under a different name.

Seen this way, the western orientation of Angkor is not an anomaly. It is a continuity.

The Khmer did not abandon Varuna’s world for Vishnu’s. They translated it. Moral oversight becomes preservation. Binding becomes holding. The sky’s judgement becomes the temple’s endurance.

To walk westward in Angkor is therefore not to turn away from origins, but to move toward the place where all forces must be reconciled. Where water meets stone. Where time closes its circuit. Where guardianship is no longer enforced, but sustained.

The West remains what it always was:

the quarter where the world must still make sense.

Also in Library

From Mountain to Monastery

2 min read

Angkor Wat survived by learning to change its posture. Built as a summit for gods and kings, it became a place of dwelling for monks and pilgrims. As belief shifted from ascent to practice, stone yielded to routine—and the mountain learned how to remain inhabited.

Why Theravada Could Outlast Stone

2 min read

Theravada endured by refusing monumentality. It shifted belief from stone to practice, from kings to villages, from permanence to repetition. What it preserved was not form but rhythm—robes, bowls, chants, and lives lived close together—allowing faith to travel when capitals fell and temples emptied.

The End of Sanskrit at Angkor

2 min read

The final Sanskrit inscription at Angkor does not announce an ending. It simply speaks once more, with elegance and certainty, into a world that had begun to listen differently. Its silence afterward marks not collapse, but a quiet transfer of meaning—from stone and proclamation to practice, breath, and impermanence.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.