Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Airavata — The Cloud That Bears the King

In the Angkorian imagination, the sky is not empty.

It has weight, memory, and patience. It arrives slowly, darkening the horizon, gathering itself before release. Airavata belongs to this sky—not as a creature that merely inhabits it, but as the sky made visible and obedient.

Airavata, the white elephant of Indra, is not an animal in the ordinary sense. He is a condensation of atmosphere and authority: thunder gathered into form, rain disciplined into service. When Indra rides, it is not upon flesh alone, but upon the weather itself.

In the oldest telling, Airavata rises from the Churning of the Ocean of Milk, born among jewels, goddesses, and poisons—a treasure whose value is not brilliance, but balance. In another tradition, quieter and perhaps older, Brahma sings over the broken shell of Garuda’s egg, and from that song the elephants of the directions are born. Airavata emerges first, followed by his kin, the Dig-Gajas, who take their places beneath the world. Space itself is propped open by their patience.

This is not fantasy. It is cosmology rendered as responsibility.

Airavata’s whiteness is not decorative. It is the colour of cloud before rain, of chalky light just before the monsoon breaks. His three heads do not multiply ferocity; they multiply awareness. He sees forward and aside, above and below—never rushing, never surprised. In some Khmer carvings he bears four tusks, a doubling of measure rather than excess, suggesting abundance that knows its limits.

In Angkor, Airavata is always near the East, where light arrives and rain is petitioned. At the gates of Angkor Thom, colossal three-headed elephants anchor the corners of the world, their trunks dipping into the naga-held waters below, plucking lotus blossoms as though the earth itself were offering tribute. These elephants do not charge. They hold.

On eastern lintels at Preah Ko, Lolei, and East Mebon, Airavata appears beneath Indra like a moving horizon—architecture briefly remembering that it was once cloud. At Angkor Wat, he emerges in bas-relief during the Churning, while at Banteay Srei he assists Indra in releasing rain to quench a forest fire, water answering fire without violence.

This is Airavata’s deeper instruction: power that arrives as relief.

Even when elephants fall in myth—when they are cursed to lose their wings and walk the earth—they do not lose their sky-nature. They become royal animals, palladia of kingship, embodiments of sovereignty precisely because they remember how to move slowly while carrying immense weight. The king who rides an elephant declares not speed, but endurance.

In Angkorian thought, Indra does not dominate the East; he tends it. Airavata is his reminder that authority must descend like rain: gathered carefully, released sparingly, nourishing rather than flooding. After Indra’s defeat by the asuras, it is Airavata who stands sentinel, stationed at the thresholds of heaven, not to strike, but to remain awake.

To stand before an image of Airavata in stone is to be taught how rule should feel. Heavy, yes—but calm. Vast, but measured. Always listening to the sky it carries.

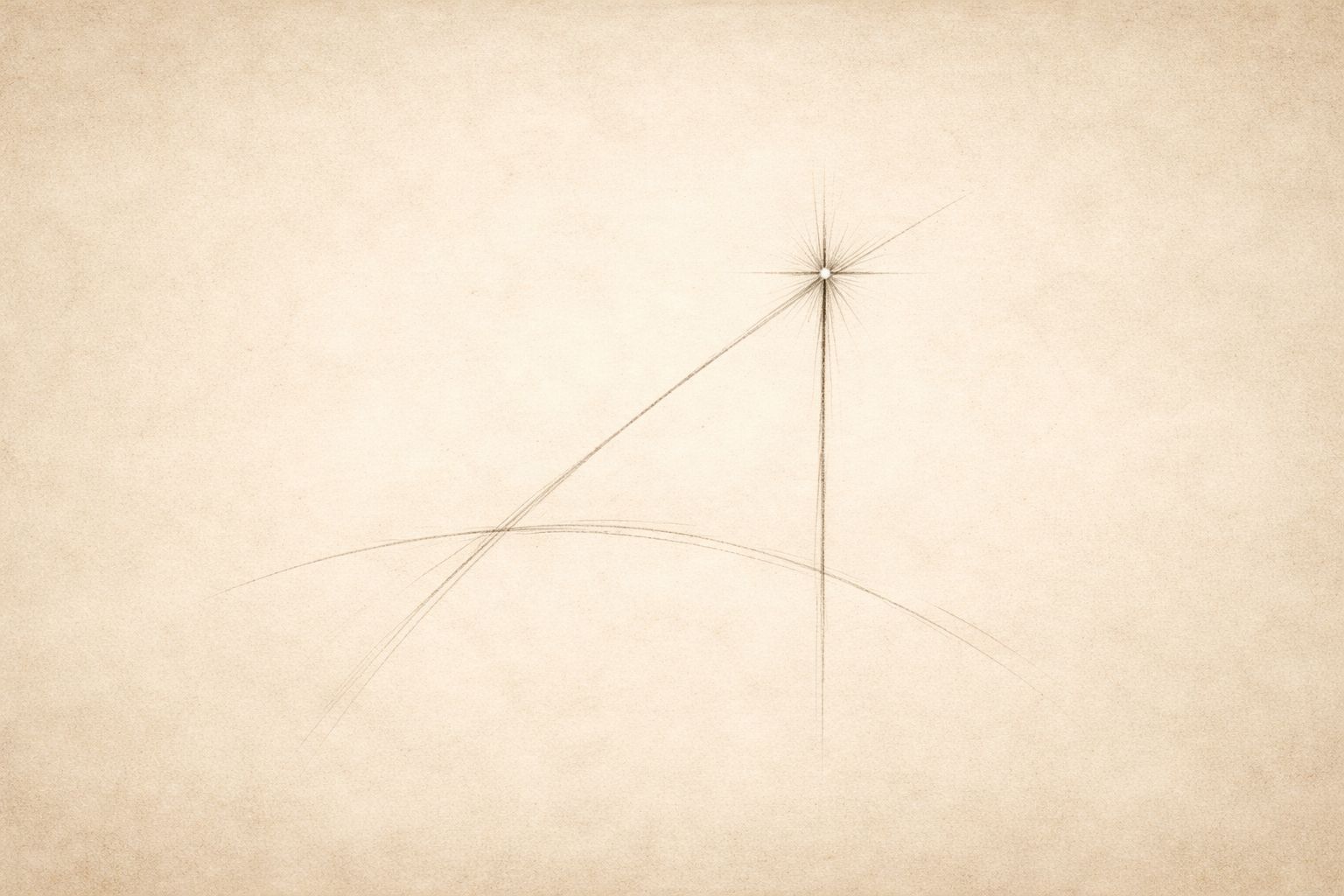

Airavata is not the king’s chariot.

He is the pause before thunder.

He is the cloud that agrees to rain.

Also in Library

The Spark and the Weight of Being Human

9 min read

At some point in our past, a human asked the first question—and self-awareness was born. Yet the same consciousness that gave us power also confronts us with our limits. This essay explores the paradox of being human: the spark of understanding and the weight of knowing.

The Pact of the Uncounted Grain

10 min read

A village does not starve only when rice runs out. It begins to thin when everything is counted, explained, and held too tightly. The Pact of the Uncounted Grain remembers an older law: that once each season, abundance must pass through human hands without measure, or the world begins, quietly, to lose its meaning.

A Manifesto for Modern Living

3 min read

The old certainties have weakened, yet the question remains: how should one live? This manifesto explores what it means to create meaning, think independently, and shape a life deliberately in an uncertain world.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap — reflections, field notes from the temples of Angkor, and glimpses into the writing and creative life behind the work.

When you subscribe, you will receive a complimentary digital copy of

Three Ways of Standing at Angkor — A Pilgrim’s Triptych, a short contemplative book on presence, attention, and the art of standing before sacred places.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet words, delivered gently.

Subscribe and step into the unfolding journey.