Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

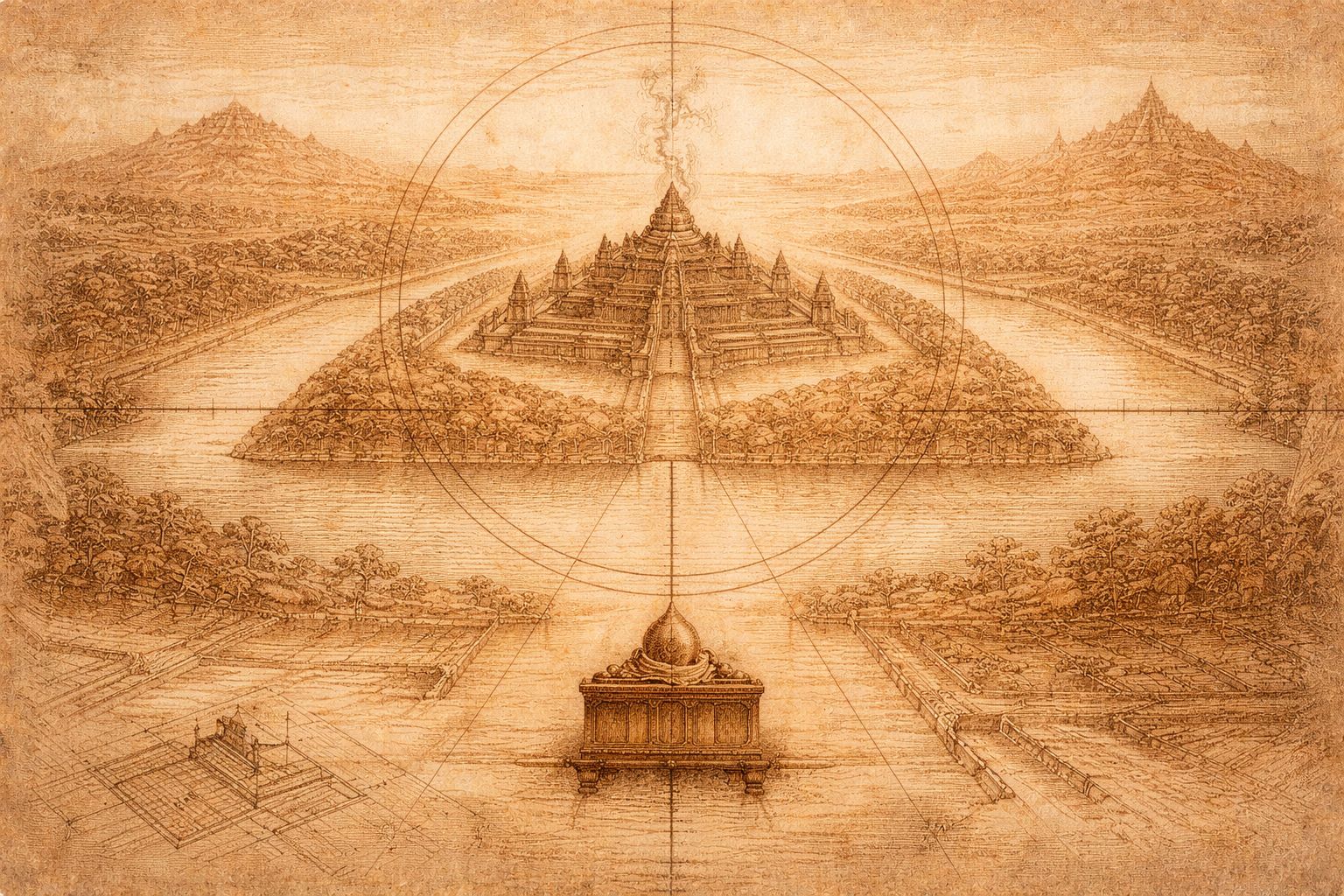

Axis, Mountain, Water — The Architecture That Held the World

Angkor was not built to impress the eye.

It was built to hold the world in place.

The Devarāja, the temple-mountain, and the baray were never independent achievements. They were conceived together, as parts of a single act of cosmological alignment—an architecture not of buildings alone, but of sovereignty, water, and time. To separate them is to misunderstand them. Each exists only because the others do.

At the invisible centre stood the Devarāja. Not a god made flesh, but a stabilising presence: kamrateṅ jagat ta rāja—the god who is king. It was the condition of kingship rather than its ornament. Established under Jayavarman II in 802 CE, the Devarāja did not glorify the monarch’s body; it authorised his position as chakravartin, the one around whom order turns. The king ruled not because he was divine, but because he was correctly aligned with a divinity that did not belong to him.

This alignment required a seat.

The temple-mountain provided it. Rising in tiers from the plain, these pyramidal sanctuaries were not metaphors but instruments—precise reconstructions of Mount Meru, the axis of the Hindu-Buddhist universe. The central tower marked the vertical line between underworld, earth, and heaven. The surrounding enclosures traced the mountain ranges that gird the cosmos. The moats rehearsed the primordial waters that surround all creation. In stone, the universe was re-assembled.

Here, the Devarāja could dwell—not as a spectacle, but as a fixed point. The central sanctuary did not house the king’s ego, but the realm’s orientation. From this height, the kingdom learned where its centre lay.

Yet a mountain without water is inert.

Meru requires an ocean.

This is where the baray enters—not as infrastructure alone, but as cosmology extended into the landscape. Vast, rectilinear, and aligned on the east-west axis, the barays were earthly counterparts to the Cosmic Ocean or Sea of Milk. They completed the mandala. If the temple-mountain was the pivot, the baray was the medium through which the world could be renewed.

The myth of the Churning of the Sea of Milk was not merely illustrated at Angkor; it was enacted. The mountain became Mount Mandara, the churning post. The waters of the baray became the ocean lashed into motion. From this controlled turbulence flowed amrita—not literal immortality, but prosperity, fertility, and continuity. The king’s task was not to dominate nature, but to regulate it: to convert monsoon chaos into measured abundance.

By controlling the baray, the king became the dispenser of life. Rice followed water. Population followed rice. Authority followed abundance. Hydraulic mastery was therefore inseparable from ritual legitimacy. The baray proved, in material terms, that the Devarāja still held.

Seen this way, Angkor functions as a single, enormous three-dimensional mandala. The Devarāja provides the spiritual charge. The temple-mountain fixes the vertical axis. The baray distributes the force outward into the plain. Remove one element, and the system collapses. Without the Devarāja, the king is merely powerful. Without the mountain, power lacks orientation. Without water, orientation cannot sustain life.

This is why each great reign marked itself not only with a new temple, but with a new reservoir. To rule universally was to re-establish the cosmos locally. The kingdom had to be re-aligned again and again—not through novelty, but through repetition of the same sacred geometry.

Even when belief systems shifted, the structure endured. Under Jayavarman VII, the Devarāja became the Buddharāja. The central axis remained. The barays still gathered water. The city continued to breathe in rhythm with the heavens. Theology adapted; architecture held.

Angkor’s true achievement was not scale, nor ornament, nor divine pretension. It was restraint. It understood that sovereignty cannot rest on the charisma of a ruler alone. It must be lodged in something slower, heavier, and more patient—stone, water, and alignment.

The Devarāja was the spark.

The temple-mountain was the spine.

The baray was the proof.

Together, they formed a civilisation that did not merely occupy land, but taught the land how to remember order.

Also in Library

The Devata at First Light

8 min read

At first light in Banteay Kdei, a devata draws the eye into stillness. Through sanguine chalk, black shadow, and repeated returns to the page, sketch and prose slowly deepen into a single act of devotion—until the words, too, learn how to remain.

The Spark and the Weight of Being Human

9 min read

At some point in our past, a human asked the first question—and self-awareness was born. Yet the same consciousness that gave us power also confronts us with our limits. This essay explores the paradox of being human: the spark of understanding and the weight of knowing.

The Pact of the Uncounted Grain

10 min read

A village does not starve only when rice runs out. It begins to thin when everything is counted, explained, and held too tightly. The Pact of the Uncounted Grain remembers an older law: that once each season, abundance must pass through human hands without measure, or the world begins, quietly, to lose its meaning.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap — reflections, field notes from the temples of Angkor, and glimpses into the writing and creative life behind the work.

When you subscribe, you will receive a complimentary digital copy of

Three Ways of Standing at Angkor — A Pilgrim’s Triptych, a short contemplative book on presence, attention, and the art of standing before sacred places.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet words, delivered gently.

Subscribe and step into the unfolding journey.