Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

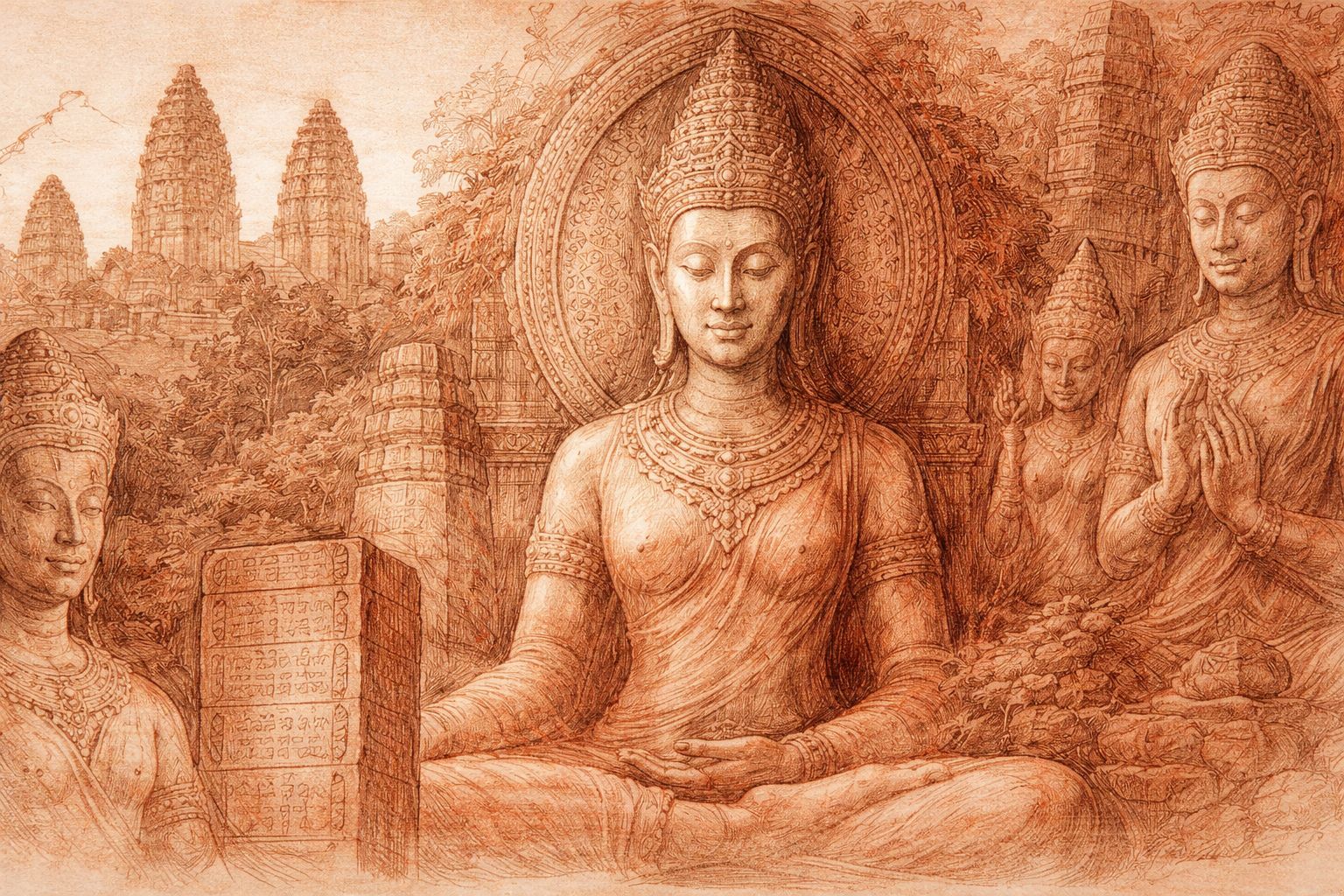

Vrah Rupa — Identity Without a Face

At Angkor, identity does not reside in likeness.

Stone faces repeat themselves with deliberate restraint: calm, symmetrical, impersonal. To modern eyes, this repetition can feel evasive, even anonymous. We search for portraits and do not find them. Yet this absence is not a failure of representation. It is a different understanding of what a person is—and what may remain of them after death.

The Khmer answer was the vrah rupa.

The term, drawn from Sanskrit and Old Khmer, means “sacred image,” but this translation is insufficient. A vrah rupa was not an image of a person. It was the conceptual body of their spiritual self, abstracted from flesh, preserved beyond mortality, and anchored within the divine order. Through the vrah rupa system, an individual—often deceased, sometimes living—was ritually identified with a god and thus granted a form of apotheosis.

This was not metaphorical. It was administrative, ritual, and enduring.

In this system, portraiture was irrelevant. What mattered was essence, not appearance. To create a vrah rupa, the Khmer did not sculpt a face remembered by the living. They borrowed a canonical divine form—Shiva, Vishnu, Lokeshvara, Prajnaparamita—and installed the individual’s spiritual identity within it. The god provided the structure. The human soul inhabited it.

This is why so many Angkorian statues appear interchangeable. They were never meant to distinguish individuals through features. Distinction occurred elsewhere—through names, ritual, and inscription.

Khmer inscriptions consistently record three separate levels of identity. First, the person as a social being: a king, a queen, a minister, a parent. Second, the vrah rupa: the abstract sacred identity of that person aligned with a deity. Third, the statue itself: the material vessel, the physical body through which the divine-human fusion could be approached, fed, honoured, and sustained.

Because the statues themselves were iconographically identical, inscriptions were indispensable. Doorway piers, thresholds, and sanctuary walls functioned as nameplates in stone. They told the informed visitor not only which god was present, but which person now existed within that god’s form.

Names were the hinge. The link between human and divine was formalised through composite nomenclature, binding an individual’s personal name to the identity of a deity. A suffix such as -ishvara or -deva aligned a person with Shiva; -narayana or -svamin bound them to Vishnu; -devi or -ishvari placed women within the body of a goddess. These were not honorifics. They were ontological statements.

Under Jayavarman VII, the system reached an extraordinary level of religious openness. Individuals whose sacred identities bore Hindu names were represented by Buddhist forms. Men were housed within Lokeshvara; women within Prajnaparamita. The statue’s iconography mattered less than the ritual intention and the name recorded beside it. Hindu ancestors could inhabit Buddhist hosts without contradiction.

What endured was not dogma, but continuity.

The vrah rupa was animated through ritual—most notably the eye-opening ceremony, in which the statue’s gaze was pierced or painted to allow the divine presence to enter. Once enlivened, the image became a yasahsariira: a “body of glory.” From that moment, the individual existed in a stable, recognisable form within the sacred economy of the temple.

This had consequences for the living. By maintaining the cult of their ancestors’ vrah rupas, descendants sustained a bridge of merit across generations. Care for the dead was inseparable from care for the future. Memory became an ethical act, and preservation a moral duty.

Seen this way, Angkor’s countless calm faces are not anonymous at all. They are precise, disciplined, and intentional. Identity here is not worn on the surface. It is spoken softly, recorded in stone at the threshold, and carried by ritual rather than resemblance.

The vrah rupa system asks us to see differently: to stop searching faces for personality, and to listen instead for names, placements, and acts of care. It reminds us that in this civilisation, a person did not survive by being remembered as they looked—but by being correctly placed within the order of the sacred.

Also in Library

The Devata at First Light

8 min read

At first light in Banteay Kdei, a devata draws the eye into stillness. Through sanguine chalk, black shadow, and repeated returns to the page, sketch and prose slowly deepen into a single act of devotion—until the words, too, learn how to remain.

The Spark and the Weight of Being Human

9 min read

At some point in our past, a human asked the first question—and self-awareness was born. Yet the same consciousness that gave us power also confronts us with our limits. This essay explores the paradox of being human: the spark of understanding and the weight of knowing.

The Pact of the Uncounted Grain

10 min read

A village does not starve only when rice runs out. It begins to thin when everything is counted, explained, and held too tightly. The Pact of the Uncounted Grain remembers an older law: that once each season, abundance must pass through human hands without measure, or the world begins, quietly, to lose its meaning.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap — reflections, field notes from the temples of Angkor, and glimpses into the writing and creative life behind the work.

When you subscribe, you will receive a complimentary digital copy of

Three Ways of Standing at Angkor — A Pilgrim’s Triptych, a short contemplative book on presence, attention, and the art of standing before sacred places.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet words, delivered gently.

Subscribe and step into the unfolding journey.