Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

Complimentary worldwide shipping on orders over $400 · No import tariffs for most countries

The Churning of the Ocean of Milk

5 min read

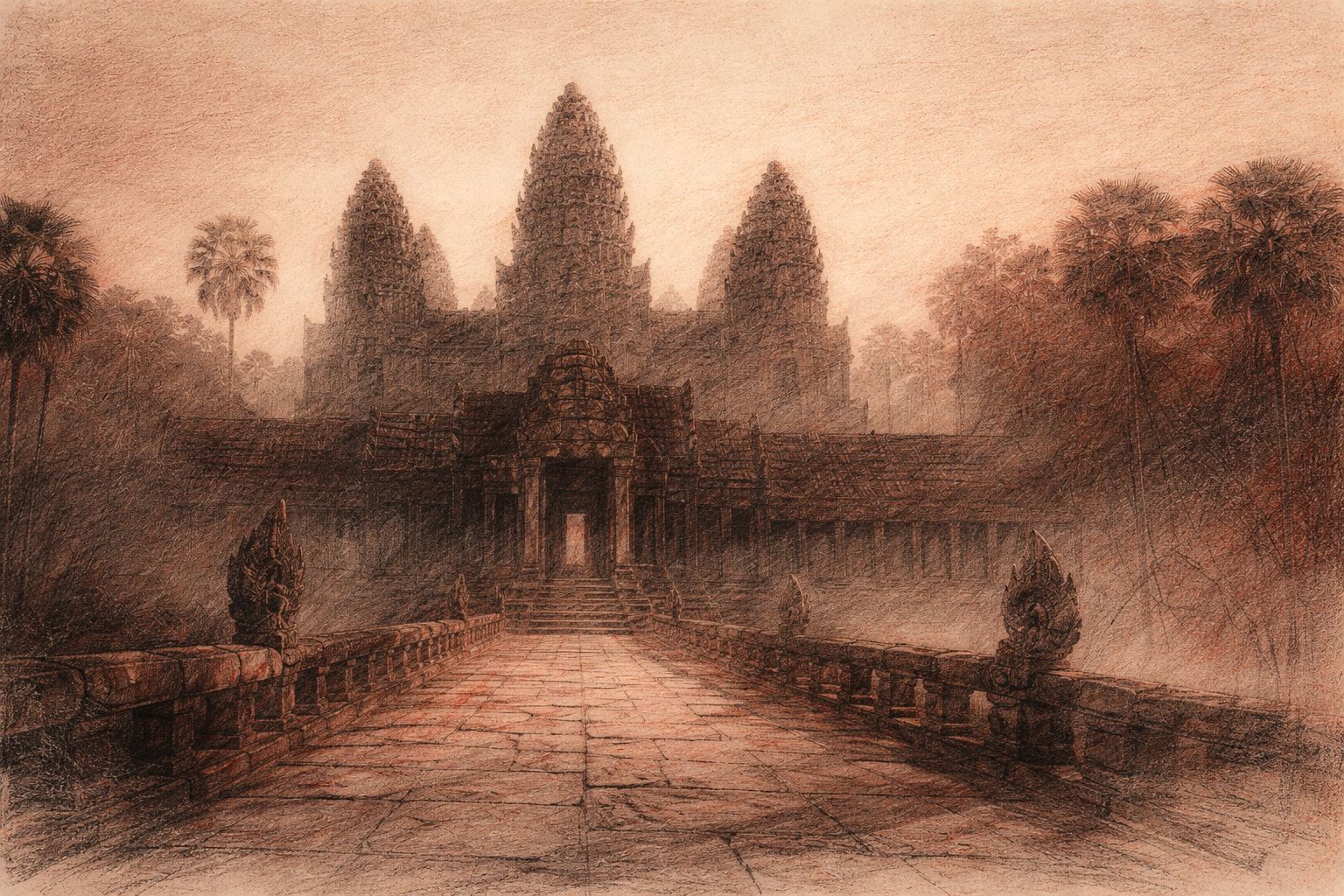

Angkor Wat as Cosmogram and Sacrificial Engine

The Churning of the Ocean of Milk unfolds at Angkor Wat not as illustration, but as cosmology fixed in stone. Carved along the southern wing of the eastern gallery of the third enclosure, extending more than forty-eight metres, the relief presents a universe under strain—its forces bound in tension, its equilibrium threatened, its renewal uncertain. In a monument celebrated for sculptural abundance, this panel is singular for its clarity of thought. No comparable relief of the medieval world so completely translates metaphysical process into rhythmic form.

The myth it invokes begins in crisis. The Earth, burdened by disorder, appeals for restoration. Dharma has failed; the balance of the worlds has tilted. The response is neither annihilation nor conquest, but cooperation under divine supervision. Gods and adversaries alike must labour together to recover amrita, the elixir of immortality, hidden within the Ocean of Milk. The great naga Vasuki is seized as rope, wound around Mount Mandara as pivot, and the long work of churning begins.

Effort alone proves insufficient. After ages of exertion, the axis itself falters. Mount Mandara sinks. At this moment Vishnu intervenes—not once, but continuously, and in multiple forms. He counsels collaboration. He stabilises the mountain. He incarnates as Kurma, the tortoise, to support the pivot upon his shell. He infuses strength into Vasuki and vigour into the opposing hosts. The churning resumes, violent enough to tear mythic creatures apart in the vortex below, sustained long enough to draw forth not only amrita, but the entire treasury of cosmic generation: Lakshmi, the apsaras, Airavata, Uchchaihshravas, the Parijata tree, the Kaustubha jewel, poison, moon, wine, and fire.

The textual traditions behind this episode—the Mahabharata, Ramayana, and Bhagavata Purana—differ in detail and emphasis. In the Mahabharata, Vishnu remains largely advisory. In later Puranic and Ramayanic accounts, he is everywhere at once: supporting, stabilising, pulling, expanding beyond perception. It is this latter vision that Angkor adopts. Vishnu appears here not as distant guarantor of order, but as the axis through which order must be continually re-won.

This multiplicity is essential. Creation, as articulated in the relief, is not a completed event but an ongoing sacrificial process. The panel is organised into three registers that mirror ritual structure. The lowest, filled with marine life and vegetal forms shattered by the churn, marks the zone of offering. The middle register—the churning itself—places Vishnu at its centre as officiant, sacrificer, and sacrificed, bound to the world through incarnation. The upper register, where apsaras drift in newly born harmony, presents the promise—never the certainty—of restored order. Mount Mandara rises through all three as sacrificial post and cosmic axis, binding underworld, earth, and heaven.

The labour is not evenly matched. On the southern side, ninety-two asuras pull against eighty-eight devas to the north. The imbalance is deliberate. Momentum favours the asuras; the crisis has not yet resolved. Creation here requires renewed intervention, renewed sacrifice. Order must be held, not assumed.

The southern flank of the panel is given to the asuras, their ranks advancing in measured rhythm. At the far end, reserve forces assemble—infantry, cavalry, chariots, elephants—arrayed across stacked pseudo-registers.

Figure 1. Asura Reserves

These formations may be read as mythic armies, but they also recall Khmer ritual spectatorship: the gathered populace witnessing coronation rites in which cosmic renewal was symbolically enacted. At the head, centre, and tail of the asura line stand three heroic figures of monumental scale. Their identities remain fluid. Multi-headed and multi-armed, they recall kings such as Bali, Kalanemi, Bana, or Ravana—figures whose destinies span death, resurrection, and perpetual opposition to divine order.

Figure 2. Bali Churning the Ocean of Milk

The leading asura anchors the pull by grasping Vasuki’s head. If this figure is Bali, the association is precise: his later resurrection through amrita binds his fate irrevocably to the churning itself. Below, the naga appears again, coiled in the ocean depths—a doubled presence that frames the composition in serpentine continuity, binding origin and action.

Figure 3. Kalanemi Churning the Ocean of Milk

Further along, another asura leader—perhaps Kalanemi—marks the rhythm. Mannikka’s solar analysis suggests this figure may represent a form assumed by Vishnu himself, participating from within the adversarial ranks. Whether accepted or not, the proposal sharpens a central insight: opposition and cooperation are not absolutes here, but interdependent forces within a single sacrificial act.

Figure 4. Ravana Churning the Ocean of Milk

Ramayanic influence is unmistakable. Figures plausibly identifiable as Ravana among the asuras, and Vibhishana or Sugriva among the devas, depart from Puranic convention yet reflect local narrative currency. The relief does not simply reproduce a canonical myth; it absorbs and reconciles living traditions.

At the base of the panel, marine creatures—nagas, reachisey, fish—are caught in the churn, dismembered by proximity to the vortex. Creation exacts cost. The ocean yields its treasures only through loss.

At the centre, the relief reaches its still point. Vishnu appears before Mount Mandara, suspended, four-armed, holding discus and club above, serpent below.

Figure 5. Vishnu Directing the Churning of the Ocean of Milk

Here the carving remains unfinished. Vishnu’s left leg is incomplete; the space below him—where the amrita and other products would emerge—lies largely blank. Faint outlines of a horse and elephant hover near the discus, perhaps later additions. The incompletion is instructive. Creation, even when held, is never final.

Above the pole, a smaller flying figure touches or steadies Mount Mandara.

Figure 6. Vishnu Stabilising Mount Mandara

This figure has been variously identified as Vishnu or as Indra. Textual precedent allows both. Identity matters less than function: the axis must be actively held.

Below, at the very base of the pivot, Kurma appears—Vishnu incarnate as tortoise—supporting the mountain upon his shell.

Figure 7. Kurma Supporting Mount Mandara

The tortoise is no incidental support. In Hindu ritual architecture it occupies the lowest layer of the altar, anchoring the cosmos. Across Cambodia, metal tortoises buried in temple foundations mark the centre of consecration. Kurma embodies creative endurance: the bearer without whom no structure can stand.

North of the axis, the devas pull in counter-rhythm. Their crowns differ, but their bodies mirror those of their adversaries. Cooperation here is strained, provisional.

Figure 8. Vibhishana Churning the Ocean of Milk

At the front stands a figure with rakshasa features—fangs, hair, stance—suggesting Vibhishana, Ravana’s brother and Rama’s ally. His presence, unrecorded in Puranic accounts, reinforces the Ramayanic inflection of the relief. Alternative identifications—Shiva, Rahu—remain possible. The ambiguity itself is instructive.

Figure 9. Brahma Churning the Ocean of Milk

Midway appears a five-faced figure, likely Brahma, though scholarly opinion diverges. Mannikka’s solar analysis again suggests a manifestation of Vishnu in deva form. The axis proliferates.

Figure 10. Sugriva Churning the Ocean of Milk

At the far end, a crowned monkey grasps Vasuki’s tail. His physiognomy matches Sugriva elsewhere in the temple, binding this scene decisively to the Ramayana. Monkey, rakshasa, god—hierarchies dissolve in the labour of restoration.

Behind him, the deva reserves assemble in ordered ranks.

Figure 11. Deva Reserves

As with the asuras, these formations may reflect ritual spectatorship as much as mythic warfare. The churning itself has been linked to Khmer ceremonial enactments—tug-of-war rites marking coronation and renewal. Indra, who loses and regains sovereignty through the myth, mirrors the human king whose authority must be ritually re-secured.

The relief offers no final resolution. Amrita is won only to be contested. Vishnu must intervene again, as Mohini, to prevent its misuse. Battle follows. Order is restored, but never permanently. The cosmos remains dependent upon sacrifice, mediation, and balance continually maintained.

At Angkor Wat, the Churning of the Ocean of Milk stands not as narrative ornament but as architectural instruction. It teaches how worlds endure: through tension sustained, axes stabilised, and power restrained by form. The stone does not describe myth; it performs it. To walk its length is to move through a cosmogram that insists creation is never complete—only held, for a time, against collapse.

Also in Library

From Mountain to Monastery

2 min read

Angkor Wat survived by learning to change its posture. Built as a summit for gods and kings, it became a place of dwelling for monks and pilgrims. As belief shifted from ascent to practice, stone yielded to routine—and the mountain learned how to remain inhabited.

Why Theravada Could Outlast Stone

2 min read

Theravada endured by refusing monumentality. It shifted belief from stone to practice, from kings to villages, from permanence to repetition. What it preserved was not form but rhythm—robes, bowls, chants, and lives lived close together—allowing faith to travel when capitals fell and temples emptied.

The End of Sanskrit at Angkor

2 min read

The final Sanskrit inscription at Angkor does not announce an ending. It simply speaks once more, with elegance and certainty, into a world that had begun to listen differently. Its silence afterward marks not collapse, but a quiet transfer of meaning—from stone and proclamation to practice, breath, and impermanence.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.

Join My Studio Journal

Receive occasional letters from my studio in Siem Reap—offering a glimpse into my creative process, early access to new fine art prints, field notes from the temples of Angkor, exhibition announcements, and reflections on beauty, impermanence, and the spirit of place.

No noise. No clutter. Just quiet inspiration, delivered gently.

Subscribe and stay connected to the unfolding story.